Pulling the Mussels

Resource managers have ejected an invasive species—for now.

by Wendy Mitman Clarke

In early spring 2018, Matthew Patterson of the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) was scuba diving in the chilly waters of Hyde’s Quarry near Westminster, Maryland, when he came upon something that made him stop in his fins.

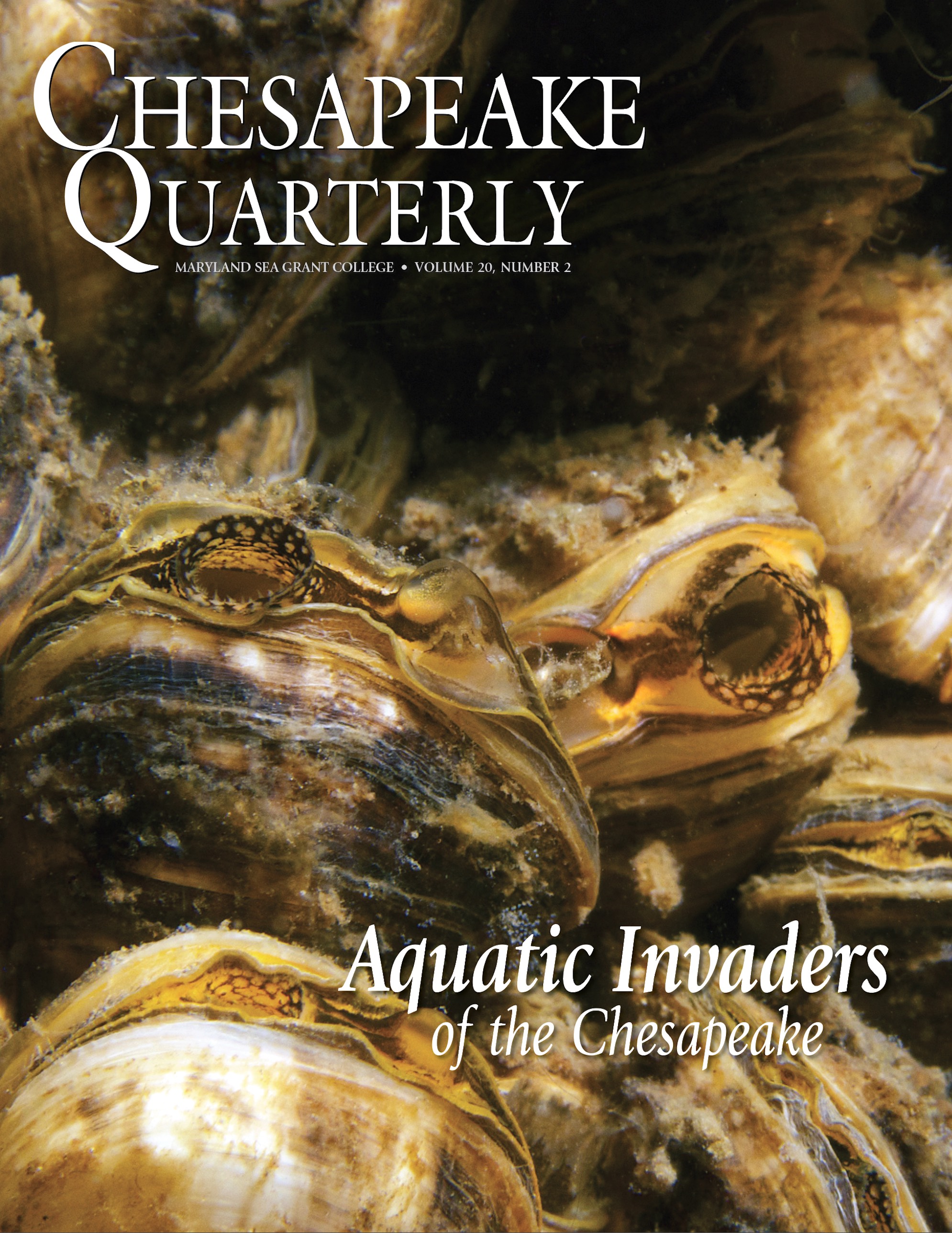

It was a small bivalve, and he suspected it was a member of the dreissenid mussels, a family that includes the famously destructive zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) and its close cousin, the quagga mussel (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis). He sent some photos to a Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) expert, and a few weeks later, three DNR divers confirmed his find, locating the mussels on a submerged dive platform and on rocks at the quarry’s southern end. They estimated the mussels were three to four years old.

Invasive mussels weren’t new to Maryland; zebra mussels first were reported in 2008 in Conowingo Pool just above Conowingo Dam on the Susquehanna River, and a year later, DNR biologists found 11 adults downstream of the dam. Since then, they’ve been regularly found on buoys and structures in the upper Chesapeake Bay as far south as Hart-Miller Island just east of Baltimore, though they have not spread as dramatically in the brackish estuarine system as initially feared.

But this was the first time that invasive mussels had been identified in a freshwater Maryland quarry. Carroll County had purchased the 8.2-acre Hyde’s Quarry in 2007 as a potential public water supply. (The quarry had been actively mined for marble until 1958, when a breach flooded it.) Though the quarry has no direct connection to the Bay, Little Pipe Creek runs only 175 feet away. If microscopic larvae, called veligers, from either mussel made it into that creek, the next stop would be Double Pipe Creek, then the Monocacy River, then the Potomac River, which supplies drinking water for much of metropolitan Washington, DC.

“The last thing we wanted to see was for them to spread from the quarry,” says Zachary Neal, hydrogeologist for the Carroll County Department of Land and Resource Management.

Diving for Answers

Zebra and quagga mussels are so similar that many resource managers use the term zebra mussel to describe both species, though research indicates that quaggas could be more destructive long-term to ecosystems. And, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS), quagga mussels are now out-competing and displacing zebra mussels in the Great Lakes and elsewhere. (For more about the differences between zebra and quagga mussels, see bit.ly/invasive-mussels). Both species have had catastrophic effects on water-based infrastructure, occluding pipes and fouling other hard surfaces. Their growth can entirely block water intake pipes to utilities such as nuclear power plants, sewage treatment systems, and public water systems. Precise costs associated with their management and control are difficult to pin down but range from the millions to billions of dollars, depending on the economic sectors and methods of calculation.

Working with DNR, the county immediately began to develop a plan to eradicate the mussels in Hyde’s Quarry. Concerned that continued public access would spread the mussels, the county notified Undersea Outfitters, the Westminster business that had provided recreational diving opportunities there since 2003, that it had 30 days to stop all quarry diving. The county closed the quarry to the public on July 7, 2018.

That same month, DNR divers collected about 350 mussels over 492 square feet going down to about 25 feet and finding “populations on the quarry walls, in cracks and crevices under rocks,” Neal says. DNR dredged part of the bottom but didn’t find mussels there. Managers estimated the potential habitat in the 115-million-gallon, 55-foot-deep quarry to be hundreds of thousands of square feet.

DNR also surveyed 1.5 miles of Little Pipe Creek but found no evidence of invasive mussels. Because the quarry has no direct access to surface water, and groundwater fluctuations determine its water level, Neal says the county also measured groundwater flow-through to determine how quickly water might be leaving the quarry. This was for two reasons: one, to assess whether flow was rapid enough that the free-swimming veligers could escape via groundwater through openings in bedrock downstream, and two, to help determine how long a chemical treatment might stay in the quarry. This flow-through was estimated between 1 to 5 percent by volume annually—“so we didn’t need to worry about them getting out too quickly.”

In August, the county created a task force to assess how best to eradicate the mussels—a science that continues to evolve as stakeholders manage established and new outbreaks worldwide. They consulted resource managers who had stopped mussel invasions elsewhere, including Millbrook Quarry in Virginia, the first open-waterbody eradication of its kind. Also a popular quarry among divers, in 2002 Millbrook became the first documented population of invasive mussels in Virginia.

According to a 2005 USFWS final environmental assessment on Millbrook, managers examined nine options to eradicate the mussels—among them injecting chlorine, shifting the pH, increasing salinity, removing the water, and injecting liquid carbon dioxide (CO2) to lower dissolved oxygen—before choosing to apply muriate of potassium chloride (KCl). Now considered a fairly standard method, this process injects quantities of KCl—commonly called potash—that essentially asphyxiates the mussels but doesn’t harm other aquatic species or humans.

Among the species common in Hyde’s Quarry are bluegills, smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, and sunfish, as well as water fleas and snails, Neal says. The county also reviewed USGS studies that evaluated the toxicity of potassium chloride to invasive mussels and non-target species.

“The studies suggested that the project target concentration would not adversely impact non-target species included in those studies,” Neal says. “Finally, we asked the Maryland DNR to review their databases and assess for the potential presence of rare, threatened, or endangered species (plants or animals) within a two-mile radius of the quarry; none were identified.” This information, along with the quarry’s possible use as a future water source, led the task force to treat with potash.

Treatment and Aftermath

After months of navigating the complex permitting process, treatment began in August 2019. First, DNR divers gathered about 4,800 mussels from the quarry to be used as in-situ bioassays to measure the effectiveness of KCl on mussel mortality. The contractor, ASI Marine, would place 43 mesh bags, with 100 mussels in each bag, at 15 monitoring stations in the quarry, which included locations and depths throughout the water column.

Among these mussels gathered for bioassay, ASI’s expert determined that about 90 percent were quaggas.

Between August 15 and 23, the team pumped 470 metric tons of 20 percent KCl solution into the quarry. It wasn’t easy. The quarry functions much like a lake, with distinct thermal layers that grow increasingly stratified as the weather warms. A thermocline—the area where the temperature and water density changes most dramatically—is located in the metalimnion, or mid-layer transition zone. By August at Hyde’s, the thermocline is at 15 to 20 feet deep.

This stratification challenged efforts to get the potassium levels consistently to the goal concentration of 100 milligrams/liter throughout the layers, particularly in the mid-levels where the thermocline held sway. Although the metalimnion concentration never was as high as in upper and lower layers, ASI’s final samples taken in November averaged 86.5 mg/L, well above the minimal lethal concentration of 30 mg/L. ASI also collected the bioassay mussels in November; all were dead.

Sampling at several sites including Little Pipe Creek and neighboring water-supply wells—once before treatment, twice during, and once after—found some increases in potassium. Concentrations ranged from 3.4 mg/L to a maximum of 12.7 mg/L, well below the 20 mg/L that the toxic materials permit issued by the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) noted as a trigger at which property owners and MDE would need to be notified. Neither the EPA nor the MDE have established standards for potassium in drinking water; the World Health Organization (WHO) notes that, “it is not considered necessary to establish a health-based guideline value for potassium in drinking water.”

Likewise, other species in the quarry appeared unaffected throughout and after the treatment.

In 2020, DNR surveyed and found no living invasive mussels. The county continues to monitor the quarry and nearby groundwater wells quarterly, and current assessments indicate that the quarry will remain lethal to mussels for up to 12 years, although Neal adds “that estimate is certainly subject to change as new information is collected and analyzed.”

The mussel eradication cost the county $365,966. In local news reports, some commissioners expressed frustration at having to fund the project while acknowledging they had little choice. There have been other costs, too. Laird Brown, owner of Undersea Outfitters, says that on a busy weekend, as many as 80 people daily would dive for fun or conduct their scuba certification check-out dives, and the annual New Year’s dive drew hundreds. Divers also patronized local hotels and restaurants. Brown says the closing “damn near put me out of business.”

The USFWS report on Virginia’s Millbrook Quarry—which was reopened to divers after the eradication there—noted that, “unintentional transport by divers from the quarry to other state waters is likely (the microscopic veligers can easily be transported in water-containing pockets of buoyancy compensators, weight belts, or other dive gear, or even on linings of wetsuits).” But Brown says that divers try to avoid becoming veliger vectors by washing gear after every dive.

Carroll County officials do not plan to re-open the quarry to the public. If they use it as a public water source, the MDE may require a lower potassium concentration than is currently observed in the quarry, which “could be achieved either through natural dilution over time, or by also partially draining the quarry until concentrations drop sufficiently,” Neal says.

Ed Rothstein, president of the Carroll County Board of Commissioners, said that while county leaders were alarmed to find the mussels, they are pleased about the outcome. “By all accounts,” he says, “the eradication seems to be successful and will also protect our environment for years to come.”

![[Maryland Sea Grant]](/images/uploads/siteimages/CQ/MD-Logo.png)