Snails, Whelks, and Snakeheads

A regional panel helps protect Mid-Atlantic waterways.

by Rona Kobell

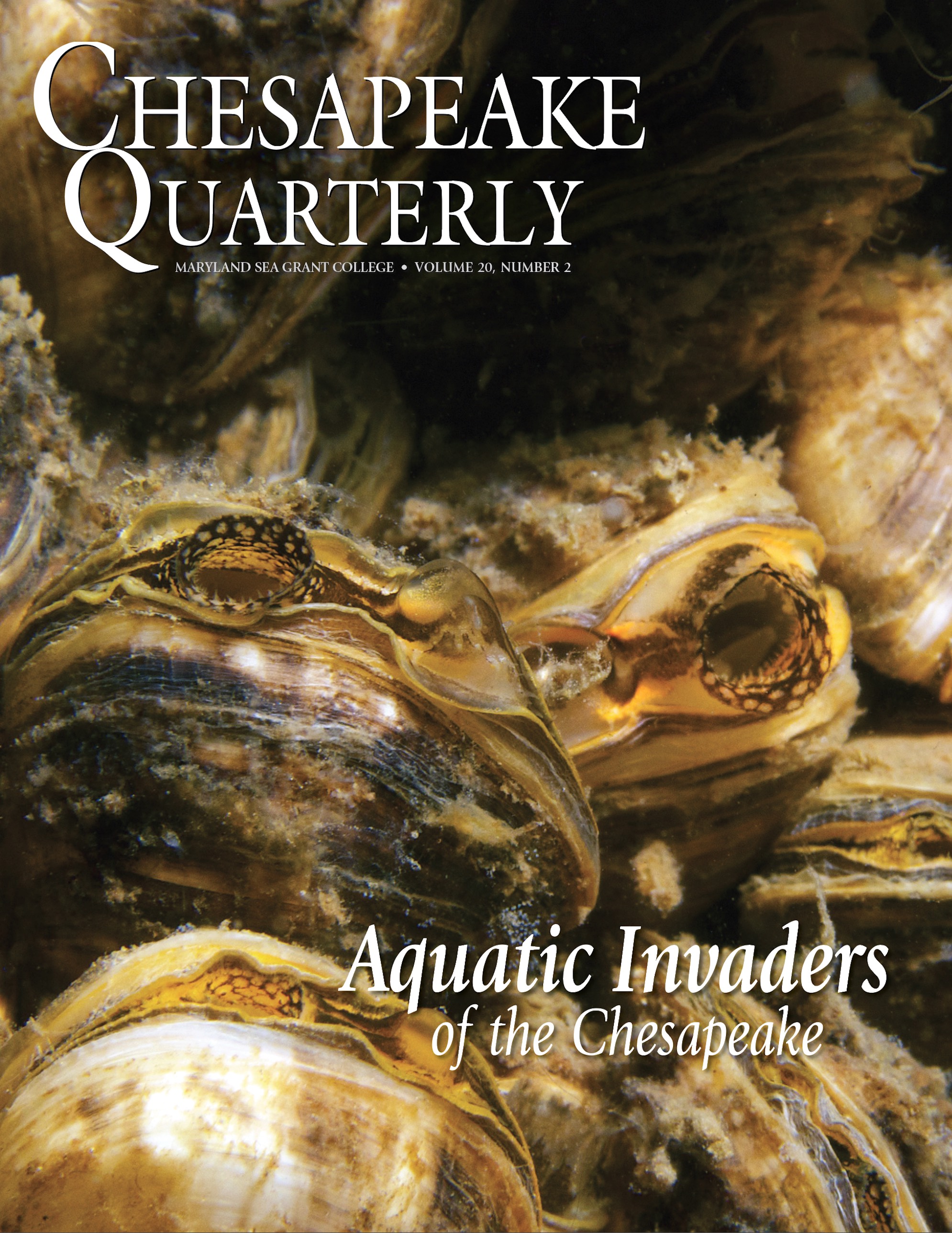

In 1998, scientists discovered that a ravenous and predatory mollusk had arrived and established a population in the lower Chesapeake Bay. The veined rapa whelk (Rapana venosa) had no natural predators. A native of the northwestern Pacific Ocean, from Japan and Korea and south through Taiwan, the whelks likely arrived in the Chesapeake by ship in ballast water; it’s common for ships to take on water in one port to serve as ballast in cargo holds or ballast tanks, then release it upon arrival in another port. The invading whelks quickly expanded their range in the Bay and devastated the already fragile wild oyster and clam populations as well as the state’s growing aquaculture industry.

Roger Mann, a marine scientist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) specializing in mollusks, wanted to work with watermen who would catch the whelks, both to remove them from the water and so the scientists could study the animals and their reproductive abilities. Many species enter estuaries, Mann said, and few become established. But those that do remain spread rapidly and are hard to eradicate, and Mann wondered if the whelk would thrive here long-term.

The Virginia General Assembly and NOAA provided funds for VIMS to offer a bounty for each whelk—$5 for every live one and $2 for the dead—to answer some of these questions. Over 12 years, watermen collected more than 22,000 rapa whelks. The work helped scientists determine their local range and reproductive cycles, provided students with experience in the labs, and cemented a close relationship between watermen and scientists in Virginia.

The collected specimens revealed something unexpected. Mann and colleague Michael Unger, an environmental chemist, discovered that tributyltin (TBT), a biocide used to coat the hulls of ships to deter hitchhiker organisms below the waterline, was present in many places where watermen found whelks. TBT also leaches into the water from those hulls, and its highly toxic chemicals can cause female whelks to grow a penis—a phenomenon known as imposex—which can lead to sterility. In 2006, Mann’s work showed a drop in whelk reproduction, which he suspected was due to TBT in the waterways.

Unger, who was studying TBT in bottom sediments, sampled where Mann had collected whelks. When he found a decline in TBT—which may have been because the shipping industry was phasing out its use—he and Mann wondered if that meant the whelk population would explode again. But because the bounty program had ended in 2008, they didn’t know.

So Mann turned to the Mid-Atlantic Panel on Aquatic Invasive Species and received $20,000 for a two-year project to ask a small group of watermen to collect whelks in particular areas where the TBT had declined, and help determine if the population was again exploding.

“Given Unger’s TBT analysis, not to go back to look at the animals would have been criminal. And when we did, it showed us that both the TBT and the anomaly had declined,” Mann said. “And now we know we should not expect this population to go away. Will they be around? Yes. Will they be an ecological and economic problem? The answer is also yes. They are here in sufficient numbers, and they are not going away.”

Turning to the Panel

Investing in researchers like Mann is crucial to keeping invasive species out of regional waterways, where they can cause billions of dollars of damage to infrastructure, wildlife, tourism, recreational and commercial fishing, and ecosystems. The Mid-Atlantic panel is one of six regional bodies that coordinate with the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force (ANSTF), an intergovernmental group representing more than a dozen federal agencies. It is the only one of the six regional panels that uses its $50,000 federal allotment to fund research projects through a competitive grants process, said longtime panel member Jonathan McKnight, an associate director at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. That, he said, makes the panel’s work both essential and effective.

“You put a little money in Roger Mann’s pocket to spend on stuff, and you are making a good investment,” McKnight said. “He knew it was a delayed system—you remove something that’s been holding them back and then, blammo . . . we can see the population blow back up.”

Veined rapa whelks are but one worry for the panel, where state representatives from Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia come together twice a year to discuss the latest invaders, relevant research, new statutes, management actions, and funding. Through the rest of the year, they stay in touch through email and occasional calls. Because invasive species do not respect politically drawn borders, cooperation is crucial. What is Virginia’s problem one year can be Maryland’s problem the next, and Delaware’s the next, and so on along the coast.

The panel’s small grants often fill the breach or kickstart new initiatives when home institutions or state agencies struggle to come up with funds; often, the small investment from the panel yields a bigger one from a university or organization when initial work shows the need for further study. One recent project in Pennsylvania created outreach mechanisms to determine the scope of flathead catfish in the Susquehanna River. A forum on aquatic invasives in lakes and a symposium on snakehead fish, both panel-funded, brought together scientists and managers to discuss invasive species across borders.

Interagency and interstate cooperation is also crucial to prevent and control invasive species because state laws vary.

“If we wanted to make something illegal in our state, there is a 26-step process. At the federal level, it may be even more complex than that,” said panel chair Edna Stetzar, a wildlife biologist with the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Her state’s laws regarding invasive species are rather reactive, she said, while others, such as Virginia, have ramped up penalties over the past five years for possessing or introducing non-natives.

Spreading the Word, Funding the Science

The panel has funded a diverse group of what McKnight says are some of the best scientists in the world, ranging from renowned experts at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center to emerging scientists at The George Washington and George Mason universities. The money supports drafting prevention plans, holding conferences and symposia, coordinating outreach campaigns, and determining best practices for eradicating invasive species on private lands. Sometimes, as in Mann’s bounty project, it funds the direct collection of the invasive species.

Mike Allen, Maryland Sea Grant’s associate director for research and administration, coordinates funding for the panel, which Maryland Sea Grant has supported since its founding in 2003. Allen said the panel is about tackling the big problems, such as predatory northern snakeheads and destructive nutria, as well as smaller successes and efforts in outreach and communications.

“It’s also us sharing updates and potential management strategies others have tried,” he said. “Those informal conversations that spread knowledge are important.”

The panel also continues to recommend providing resources to Virginia and North Carolina to eradicate their nutria populations, replicating the success of Maryland’s program on the Eastern Shore (see “Solving a Problem Like Nutria”). In 2019, it recommended the national task force ask for between $1.5 to $2 million annually for seven years to eradicate the invasive South American rodents in Virginia. It’s even recommended that Maryland’s personnel train Virginia on its eradication methods and send some resources to its neighbor, something that specialized US Department of Agriculture (USDA) canine teams in Maryland, who are trained to locate signs of nutria in the field, have said they have started and are willing to continue.

“On our own, we can push them pretty much out of Virginia, but for a long-term success, we would need the cooperation of North Carolina,” said Michael L. Fies, wildlife research biologist and furbearer project leader with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. He credits the panel with helping to push for funding in Virginia and North Carolina to work on the eradication and a strategic plan, and with helping Virginia come up with a plan that draws on Maryland’s work.

Among the recent panel-funded projects are: eDNA monitoring of didymo (Didymosphenia geminata), a freshwater diatom nicknamed “rock snot” for its appearance; the publication of Mid-Atlantic Field Guide to Aquatic Invasive Species; and a study of bloodworms and the macroalgae their trade can inadvertently bring in to local waters.

Key vectors for spreading invasive species unwittingly include recreational and commercial fishing vessels and even shoes. Didymo can spread via anglers’ boots when they go from one stream to another. Bloodworms are commonly sold in Mid-Atlantic fishing tackle stores, and their packing material can contain tiny invasives; helping proprietors understand and communicate proper disposal methods of the packaging can help keep those species out of waterways. Such education is critical, panel members said, because prevention is far easier than eradication.

“Early detection and rapid response are great, but really, you want prevention,” said Delaware’s Stetzar, “because once these things invade, it’s really difficult to get a handle on it.”

Mussels on Moss Balls

Not every aquatic species brought into the United States is invasive; some non-natives fail to thrive here. But those that do take hold can wreak unprecedented damage. According to a paper published in 2021 by researchers from Europe, South Africa, and the United States, aquatic and semi-aquatic invasive species have cost the global economy at least $345 billion since 1971. Some introductions are intentional without knowledge of consequences, like blue catfish, which were released into Virginia rivers to establish a new recreational fishery. Others happen accidentally, through the hulls and ballast of shipping vessels or when recreational boats travel between waterways and carry invaders along for the ride.

The best course of action is to keep existing numbers down, keep new invaders out, and share information about emerging threats to protect local fishing industries and ecosystems.

“All of us are working to move that needle,” said Susan Pasko, ANSTF’s executive secretary at the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), who frequently briefs the regional panels on national activities. “What are those key messages, key tools, that really work?”

Pasko’s task force had its work cut out for it in February 2021, when invasive zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) were found at a Seattle Petco store attached to aquarium moss balls—live spheres of green algae, Chladophora aegagropila. The fear was that they would enter public water systems and waterways when people cleaned their fish tanks and flushed contaminated water down domestic water pipes or into gardens, or disposed of the moss balls improperly. The task force quickly warned Washington state and then got word out to all the regional panels. Scientists with the US Geological Survey (USGS), USDA, and USFWS began contacting pet stores in every state; by early April the zebra mussels were found in moss balls in all but four: West Virginia, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Hawaii. (For more on invasive mussels, see “Pulling the Mussels.”)

Almost right away, Pasko said, states began contact tracing. Major stores, including Safeway, PetSmart, and Petco, pulled the moss balls from their shelves. The USGS’ Ian Pfingsten, a member of the Mid-Atlantic panel who works on mapping the spread of non-native invaders, tracked the moss balls to their likely source, a lake in Ukraine known to be full of zebra mussels. Because the USDA regulates plants but not aquatic pests, its officials didn’t look for the aquatic hitchhikers. Now, the USGS is looking at moss balls for other invaders, including worms and other mussels, and USFWS will be notified if more aquatic pests are found.

“Our top two priorities are to stop imports if we can and deal with what’s already here,” Pasko told the Mid-Atlantic panel at a recent meeting. The moss ball response, she added, “really is an example of how rapid response can escalate to a national level.”

For Mann, the Mid-Atlantic panel’s investment in his work could convince Virginia to resume efforts to catch the invasive whelks and try to remove them from the Chesapeake.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if there were literally tens of thousands still breeding in the Chesapeake Bay,” he said. “My suggestion is to prepare for the next wave.”

The Mid-Atlantic’s Invaders

Invasive species don’t respect state boundaries and can cause significant environmental and economic impacts. Since 2003, the Mid-Atlantic Panel on Aquatic Invasive Species—with representation from Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia—has been meeting and sharing information to try to slow the invaders’ spread. The panel’s funding helps support biological surveys, education programs, community outreach, and management of projects.

Many invasive species have been reported in multiple states. In the past decade, the panel focused on numerous issues, including the three invaders highlighted below. They’ve all been found in Maryland, as well as in other places—some close by and others several states away.

A: Rusty Crayfish

(Faxonius rusticus)

Native to the Ohio River basin, rusty crayfish have spread into the Susquehanna River as well as into the middle and upper Potomac River in Maryland. They compete with native fish and have led to reduced native crayfish populations. They consume eggs and invertebrates, diminishing biodiversity.

B: Didymo

(Didymosphenia geminata)

In 2008, this slimy-looking diatom, a native to Northern Europe and North America, was first confirmed in the Chesapeake Bay watershed in Gunpowder Falls between Prettyboy and Loch Raven reservoirs. This single-celled algae has stalks that weave together to make dense mats, which can trap sediment and smother smaller organisms, disrupting the ecology of impacted streams.

C: Northern Snakehead

(Channa argus)

The northern snakehead was first discovered in Maryland in an Anne Arundel County pond in 2002. Its regional range has expanded in recent years to the Potomac River and throughout Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Native to regions of China, Russia, and Korea, these large and voracious predators can breathe air outside of the water and can harm aquatic food webs by consuming native fish and eggs.

![[Maryland Sea Grant]](/images/uploads/siteimages/CQ/MD-Logo.png)