Seeding the Future

Maryland Sea Grant helps Greek aquaculture

by Rona Kobell

Tourists to Crete flock to the island’s aquarium, CretAquarium, in the seaside town of Heraklion to gaze at purple anemones, sinewy octopi, and a 10-legged lobster. Bilingual guides point out the glory under the glass and explain how long the creatures live, where they go, and even how they organize their social lives.

But behind closed doors, scientists are working on something less colorful and perhaps even more fascinating: how to propagate a species in aquaculture to boost the future of Greek seafood in European markets.

Constantinos “Dinos” Mylonas (left) with his longtime friend and mentor, Yonathan Zohar, of IMET in Baltimore.

Photo courtesy of Dinos Mylonas

Greece is revered for its pristine blue waters and fresh wild fish. Over the last three decades, the country has focused increasingly on aquaculture, growing fish such as gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) and European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), mostly in outdoor cages and some in recirculating aquaculture systems. Marine aquaculture is the third most important agricultural export industry in Greece, which exports 80 percent of its total output. (Aquaculture is considered a subset of agriculture.) Before its financial crisis in 2008, Greece was the leading European producer and exporter of fish, according to the Food and Aquaculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and it is still a significant producer as its economy struggles to recover. It is now the 12th major finfish producer in the world, far behind China and Norway, but well ahead of the United States, reports the FAO. The hope is to boost Greece’s struggling economy with a steady supply of fish that can feed Europe and the rest of the world.

Among the leaders in this effort is Constantinos “Dinos” Mylonas, director of research for the Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology, and Aquaculture at the Hellenic Center for Marine Research, located at the aquarium. Recently, he was the lead author on several scientific papers that presented ways to enhance reproduction in certain marine fishes using reproductive hormones — the same hormones used to assist human reproduction. One of the papers looked at striped bass (Morone saxatilis), meagre (Argyrosomus regius), and Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus), focusing on gonadal hormone manipulations and on pheromones to increase sperm secretions and egg production. Sometimes referred to as the “spawning bottleneck,” it refers to the challenge of getting fish to reproduce in captivity. Mylonas also cowrote a paper on reproduction of Atlantic bluefin tuna in captivity.

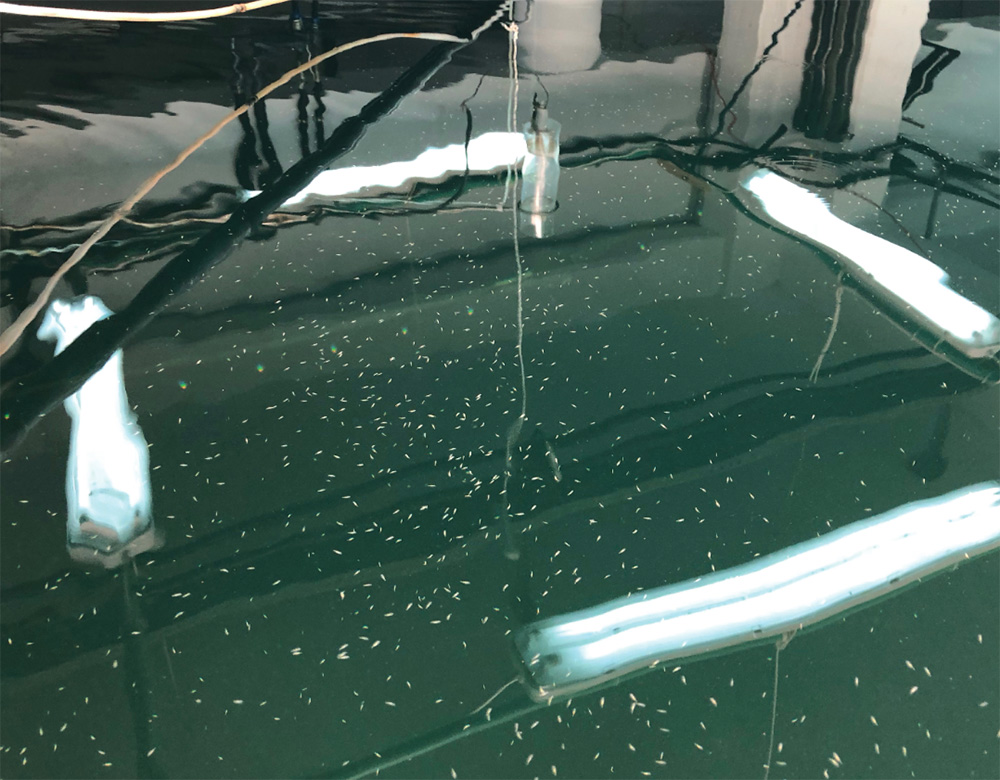

Juvenile fish (top) grow in Mylonas’s lab. Mylonas (bottom) trying to hold on to one of the lab’s more mature residents.

Photos, Rona Kobell / MDSG

Mylonas headed an EU research project involving the aquaculture of new fish species. That project, titled DIVERSIFY, consists of 38 partners from 12 countries. His lab received a $1.8 million grant to explore reproduction in captivity of two fish species — meagre, a cousin of the red drum, and greater amberjack, also known as “kanpachi” in sushi bars — for aquaculture. Results of the project, completed in November 2018, showed how to maximize efficiency in the spawning and reproductive processes.

Mylonas started his Ph.D. studies in 1991 in the lab of Yonathan Zohar, an aquaculture endocrinologist at the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute — now the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology — located at the city’s Inner Harbor. Zohar, who had come to the University of Maryland from a lab in Eilat, Israel, only a few months prior, applied for funding from Maryland Sea Grant just four days after he arrived. With it he hoped to bring in Mylonas, the young doctoral student who had sought him out while he was working in the Israeli lab. Zohar received two years of funding from Maryland Sea Grant, and he brought Mylonas to Maryland. Together the pair collected striped bass from Maryland rivers and tried to spawn the fish in captivity. They honed breeding techniques that are still used today.

“It was instrumental,” Mylonas said of the Sea Grant funding. “Without it, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. I wouldn’t have had any other means of support.”

In 1996, Mylonas received his Ph.D. from the Marine Estuarine Environmental Sciences Graduate Program at the University of Maryland, College Park. He returned to his native Cyprus for a couple of years to manage a finfish aquaculture operation. In 1999, he moved to Greece, where he is now the research director at the Crete facility.

Many days find Mylonas in his lab in front of a warren of tanks, wrangling a meagre or an amberjack to inject a hormone that will induce maturation and spawning. The fish he works with — silver, thick, and wily — are already eight years old. In the wild, they mate at five years, but in captivity they do not spawn unless treated with reproductive hormones. Mylonas and his team tackle this “reproduction dysfunction,” by helping the fish through this maturation so that they will produce large numbers of fertilized eggs. Next to the lab are small pools filled with tiny fry, the product of successful spawns. Those fish will grow and become products in the burgeoning aquaculture industry.

“We know we can control reproduction,” Mylonas said, “but is it possible to do it whenever we want, regardless of the species of fish or the rearing conditions?”

Zohar said that Mylonas, like his other international graduate students from those early days, became like a member of the family — and he still is.

“He contributed a huge amount to the Mediterranean marine aquaculture industry,” Zohar said, “overcoming that first reproduction spawning bottleneck that is so common in almost all culture fishes.”

— kobell@mdsg.umd.edu