|

Bringing the Bay into the Classroom

Daniel Strain

Maryland schools face challenges to educate

all students about the Chesapeake Bay

Katie Kramlick, a senior at Francis Scott Key High School in Union Bridge, Maryland, sees a different slice of Bay life as a painted turtle tries to nip her hand. The turtle is being kept in the high school’s aquaculture lab, which is also home to fish, crabs, and other swimming life. Photograph: Daniel Strain

THE GOLDFISH REGAINS CONSCIOUSNESS in the basement classroom at Francis Scott Key High School. First the fish, floating on its side in a plastic bucket filled with water, starts to twitch its pectoral fins. Then over a period of minutes, it rolls back to an alert, upright position.

Seniors Bree Malebranche and Alyssa Klein are keeping a close eye on this process. "We put it into — this is called a recovery bucket — and basically wait for it to regain equilibrium," says Klein, who is attending her first class of the day at this high school in Union Bridge in Maryland's Carroll County.

That class is called Science Research. Unlike a lot of traditional science courses, the students in Science Research get a hands-on introduction to what it takes to be a scientist. Here, high schoolers learn how to design scientific studies, collect data, and analyze their results.

Malebranche and Klein, for instance, are exploring the best methods for anesthetizing aquarium fish like their goldfish. They're using an agent popular with some researchers called clove oil, an extract that you can buy in drug stores. Add a few drops of this spicy-smelling liquid to a fish's water supply, and in a few minutes, the swimmer goes from awake to fully knocked out.

But getting to practice real research methods isn't the only thing that sets this class apart from ordinary high school courses. Like the two fishy anesthesiologists, all of the students in Science Research also conduct their studies on aquatic, not land-based organisms. There is a menagerie of animals stored in more than a dozen tanks at Francis Scott Key to choose from: goldfish, yes, but also tilapia, bluegill, hybrid sunfish, flounder, corals, turtles, crayfish, a blue crab, and even a four-foot-long sturgeon.

The course is one of a growing number of educational programs across Maryland that seek to introduce young students to key concepts about the watery world. Like what organisms live below the water's surface, and how do aquatic ecosystems work?

But some educators who focus on the Chesapeake Bay argue that Maryland has a long way to go: opportunities to learn about aquatic environments, and the Bay watershed in particular, still don't reach all public school students in the state. Many education leaders in the region are hopeful that developments in education policy, both at the state and national level, could put new pressure on schools to meet that need.

"It's always a zoo," says science teacher Emily Fair (above) about her Science Research class. Students like senior Mitchel Agate (top), junior Halle Fogle (third from top), and senior Patrick Mojica (fourth from top) conduct diverse studies on a menagerie of animals, including the class's star crab (second from top). Fair is helping senior Nick Amoss to fix the plumbing on one of the many tanks in this aquaculture lab. Photograph: Daniel Strain

The goal of marine educators working around the Bay is to make learning about the estuary a requirement in K-12 schools, says Tom Ackerman, an educator who works with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, a prominent nonprofit environmental organization in the Bay region: "So it's not just students at some very high-flying suburban schools that get this opportunity, but all students."

Death and Oddities

School teachers are notoriously busy people, but Emily Fair's life seems to run at a whole other level of crazy. She's a teacher at Francis Scott Key and is Malebranche and Klein's instructor in spring 2014 in Science Research.

Right now, she's bouncing between teams of students in the high school's aquaculture lab, which isn't much bigger than a two-car garage. The noise of chugging water pumps and gurgling filters floods the room. There are all sorts of tanks here: they range in size from the kind of aquaria that you can find at pet stores to two 1,000 gallon drums that together could hold the water from four standard hot tubs.

And all of them contain some sort of animal. The roughly 30 students in the Science Research class are studying these critters to learn, for example, how flounder camouflage themselves to escape predators, why crayfish cannibalize one another, and how loud noises affect the growth of young fish. There's always something interesting to see here. When the lab's one blue crab, a male that's almost big enough to be on the menu at a seafood restaurant, molted, Fair collected the exoskeleton that it left behind.

"This is going on my table of death and oddities," she says, referring to a countertop where she keeps biological artifacts that she thinks will capture the attention of teenagers.

The Science Research program was launched more than two decades ago at South Carroll High School in Sykesville, which like Francis Scott Key is part of the Carroll County School District. Since then, aquaculture labs like Fair's have spread to all nine high schools in the county and in a reduced form to some middle schools. The county is the only district in the state that has made aquaculture labs a permanent fixture in so many schools. All of these schools are permitted through Maryland's Department of Natural Resources to keep these animals for aquaculture education purposes.

The district receives funding and technical support for these labs from Maryland Sea Grant, the publisher of Chesapeake Quarterly. The program also benefits from assistance and surplus equipment donated by staff at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology in Baltimore and grants from other organizations.

Fair has only been teaching Science Research since the 2011-2012 school year, but she fits right into this environment. She's quick to smile and joke with her students and has seemingly endless supplies of energy.

Her lessons about the scientific method include reminders that research projects don't always go as planned. Early in the semester, all of the tilapia in one of the lab's 1,000 gallon tanks came down with a weird infection and died within a few weeks. "Students need to be able to embrace failure," Fair says, "because then they learn from that."

She also takes the time to connect what students are studying in this lab setting back to the natural world. Her pupils, for instance, learn that fish in a tank can only survive under a certain range of environmental conditions. If ammonia levels in the water get too high, or oxygen levels too low, the fish can become sick or die. Fish living in the Chesapeake Bay face similar restrictions: as humans dump nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus into the estuary, the water quality in the Bay deteriorates, with real-world consequences for many animal populations.

The course seems to be paying off, too. Lauren Cheeks is a senior at Francis Scott Key who's taking Science Research for a third semester. (Students are allowed to enroll in up to four semesters of the course.) In the 2014-2015 school year, she'll be a freshman at Shepherd University in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. "Everyone who takes this class changes what they want to be when they grow up," Cheeks says. "I wanted to be a large animal vet. Now, I want to work in marine studies."

She isn't the only person who sees the value in these sorts of classes.

Sturgeon Experiences

Learning about the marine world isn't just a potentially life-changing experience. It's also a necessary part of a student's education.

That's the argument made by Craig Strang, associate director of the Lawrence Hall of Science, a museum and education center that's part of the University of California, Berkeley. Strang is also one of roughly 1,100 members of the National Marine Educators Association, an organization that draws representatives from schools as well as aquariums. For decades, he says, marine science has largely been squashed out of school curricula in favor of other subjects — cell biology, inorganic chemistry, particle physics, and other textbook topics. But Strang argues that science teachers should make room at the table for the watery world.

Aquatic ecosystems are central to the workings of our planet, notes Michael Wysession, a seismologist at Washington University in St. Louis. Wysession has helped to write a number of reports on national science education policy and pushes for science teachers to focus on "earth systems." In other words, the earth has many parts — like its atmosphere and crust — that interact with each other to drive the climate and other natural processes. Think of them like the cogs and gears that underlie the ticking of a watch. And aquatic environments are a critical component of that timepiece.

"Oceans dominate the Earth's surface. You can't avoid having the oceans play a dominant role" in topics related to how the planet works, Wysession says. "Whether it's transferring energy, heat around the planet, or whether it's controlling the water cycle."

But for Marylanders, there's another reason to include marine and aquatic science in a child's education. Young learners often jump at the chance to get outside and see living plants and animals up close. Such excitement can, in turn, help interest kids in learning more about science — a subject that can seem intimidating at first to many students.

"The formal education community has known for a long time that if the student has some emotional connection to [educational] content, they're going to be excited about it. They're going to learn more," says Marc Stern, a social scientist at Virginia Tech who studies the efficacy of education programs that focus on the environment. "And it just so happens...they're likely to take action" to protect local habitats.

And in a state with nearly 3,200 miles of coastline, the local environment in Maryland revolves around water. That's true even in land-locked areas like Carroll County, where small streams feed into bigger rivers that eventually empty into the Bay. About 70 percent of Maryland's population and land lies in the state's coastal zone.

"I'm just struck with the incredible, incredible resources that the Chesapeake Bay provides to a very large and dense population on the East Coast," Strang says.

In school districts like those in Montgomery, Prince Georges, and Anne Arundel counties, those rich teaching resources include the districts' own environmental education centers. These are at off-campus sites where students can go on hikes or other field adventures to learn about the local environment.

In other cases, non-profit groups have designed educational opportunities that school districts can take advantage of, usually for a fee. Teachers can arrange for their classes to take a boat ride down the Potomac River with educators from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF). Students can raise terrapin turtles in their own classrooms with assistance from staff at the National Aquarium in Baltimore. Kids from southeast Washington, D.C., can learn about marsh plants on Kingman and Heritage islands on the Anacostia River as part of programs organized by the Living Classrooms Foundation, a non-profit group based in Baltimore.

The list goes on and on. "I think we're a little bit spoiled in this region," says Tom Ackerman, the educator at CBF.

In many cases, these programs are popular with parents and other community members, too. Twice a year, they flock to high schools in the Carroll County district to open house nights that feature Science Research students, says Brad Yohe, who helped start the program. He served as a science supervisor in the district before retiring in 2012. Students present their research projects at these events. During one at Francis Scott Key three years ago, he remembers seeing a student of Emily Fair's lift a sturgeon out of its tank to show the audience, which included her family.

"The student brought up this four-foot-long sturgeon and put it in the lap of her grandmother who was in a wheelchair and explained her project," Yohe says. "The looks on their faces — it was a photographic moment."

But it's a type of photographic moment that thousands of students in Maryland still never get to see. No statewide assessment has been undertaken to gauge how many students get the opportunity to learn about the Bay in a hands-on manner every year. But it's clear that the number is less than the more than 800,000 students who enroll in Maryland public schools.

Many educators in the state are looking for ways to provide even more students with access to a Bay education. To that end, teachers and others have their eyes on some big changes in the educational world that might help that to happen.

The Next Generation

Over the next several years, Emily Fair and other teachers like her in Maryland could see big shifts in the way science is taught in the state — not just when it comes to marine science but also physics, chemistry, biology, and a host of other subjects. These changes come down to one thing: standards.

Think of educational standards like the map you take on a long road trip. They detail, in a step-by-step fashion, how students should reach certain education goals and by what grade. Young learners start by absorbing basic concepts, then move onto more complex ones. School districts, like the one in Carroll County, use these maps to shape their curricula. They choose lessons that they think will help students to meet the requirements set out in standards.

So when the Maryland State Board of Education voted in June 2013 to adopt a new set of science education standards for the state's 24 school districts, big changes seemed to be afoot for local classrooms.

The new requirements are dubbed the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). They're based on the work of a team of education leaders and researchers assembled by the U.S. National Research Council and were released in their final form earlier that same year.

Under the NGSS, second graders, for example, are supposed to gain an understanding that "wind and water can change the shape of the land." By the time a student reaches middle school, they're onto a more sophisticated elaboration on this idea: "global movements of water and its changes in form are propelled by sunlight and gravity."

But the new Next Generation standards also represent a relatively new focus in science education. They rely heavily on a particular teaching tool, something that educators call "inquiry," says Gary Hedges, who oversees science education policy at the Maryland State Department of Education.

Inquiry-based approaches to education shy away from having students memorize long lists of facts, instead encouraging them to learn for themselves through hands-on activities. That can include running experiments, drawing diagrams, or completing other classroom projects. The NGSS, for instance, requires high schoolers to "design, evaluate, and refine a solution for reducing the impacts of human activities on the environment and biodiversity."

"It takes the teacher off the stage and really puts them in a facilitating role," Hedges says.

As of December 2014, 12 other states plus the District of Columbia had joined Maryland in adopting the Next Generation standards. The state plans to have all school districts come up with curricula that meet the requirements set out in the new standards by the 2017-2018 school year. But some science educators in Maryland are already looking forward to the shift, with expectations that the new standards may foster learning opportunities that address the Chesapeake Bay.

The NGSS could encourage the teaching of more marine science content than most schools are used to providing, says Craig Strang of the Lawrence Hall of Science. That might be hard to grasp just by picking up the new standards and flipping through them. Read the text, and there are few direct mentions of aquatic ecosystems.

But the standards embrace an "earth systems" approach to learning about the planet — the same approach championed by Michael Wysession of Washington University. In fact, the seismologist served on the team that wrote the NGSS. Because students need to know how the oceans work to understand complex topics like climate change or the water cycle, "ocean systems can come into a huge number of those performance expectations" under the NGSS, Wysession says.

Despite this potential sea change, the NGSS are just one example of a potentially promising new approach to science education in Maryland.

The Story of Cocktown Creek

To see another one, head south from the green farms and rolling hills of Carroll County to the marshes and cliffs bordering the Chesapeake Bay in Calvert County.

There, at the edge of Cocktown Creek, Tom Harten sits in the middle of a flotilla of canoes. They are lined up along a grassy bank of the creek, a small waterway that empties into the Patuxent River. Harten, a veteran science teacher, is vying for the attention of 15 adolescents and a handful of adults all wearing brightly-colored life preservers. "Dad, I found a snake," one student shouts.

Harten's audience today are seventh graders from John Pellock's science class at Plum Point Middle School in Huntingtown, Maryland. They're taking part in a program called CHESPAX, which gets its name from a mash up of the words "Chesapeake" and "Patuxent." This series of educational activities has been a mainstay of the Calvert County School District since 1988. Students in kindergarten through seventh grade get the chance to learn about the Chesapeake once a year — digging, sometimes literally, into the estuary's history and ecology.

All fourth graders in the county, for instance, visit Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons, where they handle fossils that have been found along the Bay. All fifth graders travel to the county's Fishing Creek or Flag Ponds Nature Park to learn about oysters and their influence on water quality in the region. So far, Calvert County is the only school district in the state that sends students in all these grades on such excursions every year.

Today, the seventh graders jostling around in the canoes will use small rakes that look like back-scratchers to collect submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV, from Cocktown Creek.

These grasses sit just below the surface of the water, and this year, they're growing in clumps so thick that you can barely push your oar through them. This underwater grassland — made up of plants like hydrilla, coontail, and naiads — is prime habitat for small crabs and other swimming life.

The students will help to map out where you can find SAV in the creek and what species are most common. That information is relevant to the day-to-day lives of these students, says Harten, who's been a teacher with CHESPAX for more than two decades. Human activities, such as building houses or roads, can flush sediment into streams like this one, turning the water muddy. When that happens, those grasses struggle to soak up sunlight and may eventually die off.

"This creek basically drains the town where a lot of you live," Harten says from his perch on the seat of his canoe.

The students, many turning pink from the sun, also seem excited to see some of the concepts they've been studying in Pellock's class up close. "It's cool that we're learning about SAV," says seventh-grader Josh Hancock, who sits in the front of one of the canoes, "actually seeing it in the wild rather than just learning about it in the classroom."

Seventh grader Ariana Smith (above, black t-shirt) and Madeline Freck (above, red t-shirt) are visiting Cocktown Creek in Calvert County, Maryland, as part of the county's CHESPAX program. First the two classmates use a device called a transparency tube to measure Secchi depth (clarity of water) in samples collected from the creek. Later, Smith and Freck drag a seine net along the beach (above, right) to see what sort of swimming animals live in this waterway. Tom Harten (below and above left with Smith and Freck) is a science teacher who has been leading CHESPAX trips for more than two decades. Photograph: Daniel Strain

His response shows why marine educators in the state would like to see more of this type of educational opportunity in Maryland. But there are huge challenges to making that happen.

That's largely because launching an educational program like CHESPAX or Carroll County's Science Research courses takes a lot of work — on the part of school districts, principals, teachers, and others. Maryland is also a "home rule" state when it comes to education. That means that each and every county in the state draws up its own curriculum, based on standards, and would have to create its own version of CHESPAX.

The end result is that if schools don't have to develop these sorts of programs, many won't, says Brad Yohe, the former science supervisor from Carroll County. He explains that he tried during his tenure to get other school districts interested in setting up their own aquaculture labs. He had few takers.

"You can be a science supervisor and do all the things you have to do for the county and never do" a program like Science Research, Yohe says. "And you'll be fine and successful, and you'll save yourself a lot of work."

One solution to that problem is for the state of Maryland to make teaching students about the Bay mandatory, says Tom Ackerman, the educator from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

Maryland is getting closer to that goal. In 2011, the state's Board of Education passed a new set of standards called environmental literacy standards. The aim of these requirements is to ensure that all students in the state get access to quality educational experiences that focus on the environment.

In practice, the environmental literacy standards require schools to provide their students with yearly opportunities to learn about using science to solve various problems. Aquatic habitats are called out in the regulations that put the standards into place: under the requirements, students need to understand how they can "preserve and protect the unique natural resources of Maryland, particularly those of the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed." Before they graduate from high school, all Marylanders will receive chances to explore environmental issues and come up with ways to address them.

These standards went into effect in the 2011-2012 school year. They put Maryland on a short list of states that have made education about the environment such an important part of school curricula — something that educators who were already teaching students about the Bay saw as a victory.

"It definitely validates what they do," says Melanie Parker. She coordinates the environmental literacy programs at the Arlington Echo Outdoor Education Center in Millersville, Maryland. The center is part of the Anne Arundel County School District.

Like other school districts in the state, Anne Arundel County is taking steps to adapt its curricula to meet these requirements, Parker says.

Arlington Echo, for instance, runs an educational program called Chesapeake Connections that helps students to explore the Bay through a variety of hands-on activities. That might include raising American eels in the classroom or going outdoors to do projects to restore local habitats. Before the new standards went into effect, that program was optional. If elementary and middle school teachers wanted their classes to take part, they would have to sign up through the center. Now, it's part of the school year for all sixth graders. That ensures that "we hit every single student in the county," Parker says.

In 2015, the Maryland State Department of Education will conduct its first evaluation of the progress that counties have made toward meeting the new standards.

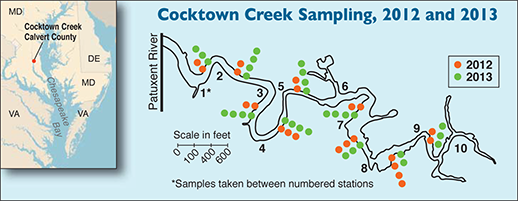

The more than 15 years of observations made by seventh graders from Calvert County on Cocktown Creek have tracked changes in the waterway over time. The map above compares the number of diverse species of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) the students found in the creek in the fall of 2012 and 2013. In the first year (orange dots), the numbers plummeted after a series of storms hit the region. By fall 2013, SAV populations had begun to increase (green dots). The loss of SAV diversity may have been caused by the cloudiness of the creek water, which the students measured as “Secchi depth” (graphs, below). The greater the Secchi depth, the clearer the water — allowing more sunlight to reach growing plants. Map of Cocktown Creek and graphs, adapted from a figure and data used courtesy of the CHESPAX program; map of Chesapeake Bay, iStockphoto.com/University of Texas Map Library

Making the Commitment

As with any education push, schools in Maryland will need a lot of resources in order to meet the requirements laid out in the state's environmental literacy standards and the Next Generation Science Standards.

Or, as Brad Yohe puts it, "what we need are more lessons."

Many science teachers, for instance, have little experience with helping their students carry out investigations of environmental issues. What sort of experiments can students reasonably conduct in a classroom setting? And how do teachers evaluate this work?

That's where lesson plans come into play: lists of classroom activities like experiments or art projects that have been designed to touch various objectives in education standards. School districts can pick and choose from among these activities and add them to their curricula. When it comes to the NGSS, there are a lot to choose from. Because these standards will reach so many students, large numbers of education groups have already put together lesson plans on an array of topics that align with the NGSS.

But because Maryland's separate standards for environmental literacy are only statewide, not national, fewer resources exist to help school districts meet these requirements.

RICKY CATRON, TIM BOWERSOX, AND EMILY KEITH spend many mornings in a science lab tucked into a corner of North Carroll High School. Here, you can find a diverse array of equipment: computer monitors, an electronic device called a “breadboard” that’s bursting with wires, and a fish tank complete with a toy tiki hut and a spotted goldfish named Bessie. more . . .

Luckily, that's something that marine and environmental educators in the state are keenly aware of. The need for better environmental lesson plans in the state, for instance, drove the formation of the Maryland Environmental Literacy Partnership. This collaboration includes the state's Department of Education, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, and the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. During the 2014-2015 school year, the partnership is working with nine school districts in the state to test out a series of lessons, or "modules," that focus on the workings of the Bay watershed.

These new modules include one that asks high schoolers to answer the question "how do humans impact the water quality of your local region of the Chesapeake watershed." Requiring around 14 to 17 hours of class time, this module allows educators not only to check off several boxes under the environmental literacy standards but also hit six points in the NGSS — "evaluate or refine a technological solution that reduces impacts of human activities on natural systems," for one. Among other activities, students taking these modules learn how to make a topographical map using cardstock and create a budget for how much water they use at home and school.

In the end, however, new standards or lesson plans alone can't drive schools to create programs like CHESPAX or Science Research, Yohe says. That takes something more intangible: a culture shift in the school district. In other words, teachers, principals, and other administrators need to lend their full support to a new educational approach. And be willing to put in the extra time and money that it takes to set up something like an aquaculture lab.

Today, Fair's main task is to figure out what's gone wrong with one of the lab's pumps, which stopped working recently, requiring her to "don my electrician's hat."

DO YOU WANT TO HELP young learners explore the Chesapeake Bay and other marine environments? It can be tricky to know where to start, so we’ve put together this list of selected Bay and marine education resources that can be found online. more . . .

Still, once Yohe got the Science Research program off the ground, "the rewards were worth all the effort," he says.

Emily Fair is one of the motivated educators who keep the Science Research program afloat. It's July and she is back in the aquaculture lab. With school on summer break, the room is a lot quieter. But Fair and a handful of student volunteers are still coming in about once a week to clean the tanks and do other upkeep tasks.

In the end, she says, it's all worth it. She still remembers the first time she saw this aquaculture lab years ago. She was getting her bachelor's degree at McDaniel College, which is also in Carroll County, and was working as a student intern for a biology teacher at Francis Scott Key. One day, her mentor told her that she needed to check out the school's lab down the hall. "I walked in," Fair says, "and I knew then and there that I wanted to be a part of this."

NOTE: A previous version of this story incorrectly reported certain details about Anne Arundel County's environmental education program. The story has been modified to reflect the fact that all sixth graders are required to take part in the Chesapeake Connections program, offered through the county's Arlington Echo center. The examples of activities that these students take part in have also been changed.

|