Urban Watershed

Contents

Beneath the vroom of traffic on Russell Street, the mouth of an outflow pipe yawns into the Middle Branch of the Patapsco River. Hidden under this busy Baltimore thoroughfare, the 25-foot-wide masonry pipe opens onto garbage-lined banks. Plastic bags and newspaper hang from drooping tree branches. Styrofoam containers bob in sickly green water.

That is just what's visible. Unseen are loads of unsavory substances — heavy metals, bacteria, nitrogen, and phosphorus, not to mention millions of suspended particles that bind toxics tight. This spoiled backwater flows under a crisscrossing tangle of highway overpasses before emptying its load into the main expanse of Baltimore Harbor. Out of this pipe flows some of the dirtiest water heading for the Chesapeake Bay.

They call it pipe 263.

Pipe 263 drains untreated stormwater from the most urban of urban watersheds. It's filled with pollutants that wash off streets and sidewalks or seep into the system from illicit sewage connections. Far from the Bay itself, the pavement here stretches in concrete waves and crabs come only as carry-out. Watershed 263 doesn't harbor a single flowing stream. Not one rocky streambed. No fish. No water striders. No ducks.

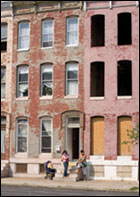

Watershed 263 is more accurately a "stormshed," an antiquated system of underground pipes that carry away stormwater coursing off Baltimore's city streets. Named simply for the giant pipe at its terminus, Watershed 263 drains 930 acres encompassing twelve neighborhoods in West Baltimore. Few trees dot the landscape — too few to support even birds and squirrels, the hardiest residents of an urban forest. If not for the vibrant colors of Baltimore's rowhouses, Watershed 263 would be a very gray place.

On Lanvale Street, Matt Cherigo pulls on latex gloves and a Tyvek suit. He's getting ready to climb into a storm drain in the mid-watershed neighborhood of Harlem Park, where he works as a field technician. His two assistants, Emma Noonan and Melissa Grece, are hooking up a barrel-shaped, automated water sampler to a steel cable. Cherigo's head is uncovered. He forgot to order the suits with hoods.

The day's forecast warns of heavy rain and the air hangs low. That's why Cherigo and his field team are taking water quality samples from the Lanvale storm drain, as well as from another storm drain at nearby Baltimore Street. Over the last four years they've sampled each major storm event and taken baseline samples every two weeks from the two sites. Cherigo works for the Dundalk, Maryland-based contract lab called Microbac, but the overall sampling effort is conducted through a partnership between the Baltimore Department of Public Works and the Baltimore Ecosystem Study, a project that studies urban Baltimore as an ecological system. The water samples are analyzed for levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, bacterial load, and heavy metals. The resulting data make up the first quantitative record of stormwater quality from an ultra-urban area within the Chesapeake watershed.

Cherigo cleans rust off battery terminals on the automated sampler and programs the computer. He's going to anchor the sampling device inside the storm drain, where it will remain through the duration of the storm. Rising water levels inside the storm drain will activate the automated sampler. The trick is to get the sampler in place, then get out of the way before the storm hits.

Stormsheds like Watershed 263 interweave much of Baltimore City's subterranean landscape. There are 114 outflow pipes like pipe 263 that deliver untreated stormwater directly into Baltimore Harbor or the Patapsco River. In Watershed 263, as urban growth paved over natural streams, city planners built a 43-mile network of 355 storm drains to funnel water out of the city. Like the natural streams they replace, many of these storm drains have base flow, even in dry weather. Due to a deliberate structural decision to leave the joints leaky, groundwater percolates into the pipes - an engineering solution designed to shunt water away from basements and house foundations.

The water that flows beneath Baltimore's streets contains concentrations of nitrate comparable to the region's agricultural areas (nearly 6 milligrams per liter during low flow periods). And levels of lead, copper, and zinc routinely exceed the Environmental Protection Agency's legal levels during storm events, according to water quality monitoring data.

This stormshed has actually been defined as a watershed based on water flow patterns (hydrology). And it's being managed as such.

|

This pilot project is the first of its kind — a joint effort begun in 2004 between the Baltimore City Department of Public Works and the Parks & People Foundation, a nonprofit Their goal: to enlist the community in restoring water quality and "greening" the watershed. Their plans focus on reducing impervious surfaces, growing the tree canopy, cleaning streets and alleys,

and creating biofiltration sites by cleaning and landscaping vacant lots and schoolyards — all to improve the health of the community and water quality in Watershed 263.

|

It's daunting. Life is hard in the neighborhoods within this watershed. Residents grapple with economic hardship, crime, drugs, and homelessness. Block after block, houses stand abandoned. In some neighborhoods, the number of unoccupied homes exceeds one in three. The median income of the watershed is $20,000 and unemployment tops 60 percent. In these neighborhoods, no streams flow through urban parks. The stormwater pipes that drain into Baltimore Harbor hide out of sight, buried deep under asphalt. The Chesapeake Bay — its flat expanses of water, its marsh grass, and its osprey — seems a distant world. Given this gaping disconnect between city and Bay, can the people of Watershed 263 come together to improve the health of the urban environment? Can they help clean the waters that flow through hidden streams?

![[Maryland Sea Grant]](/GIFs/h_footer_mdsg.gif)