Urban Watershed

|

|

|

At the bottom of the square-shaped storm drain, Cherigo's white Tyvek suit lights up the dark tunnel. He shouts numbers to Noonan and Grece as they record background measurements and qualitative descriptions of conditions in the drain.

Cherigo is still in the hole when Bill Stack arrives. Dressed for the weather in a long gray raincoat, Stack pauses briefly to answer a quick email on his Blackberry before heading toward the storm drain. The sampling efforts in Watershed 263 hold intense interest for Stack, the water quality chief for the Baltimore City Department of Public Works. Stack's the one who manages pollution control efforts for the city's stormwater, the one charged with making things better. He needs a way to assess whether community greening and other Best Management Practices (BMPs) are actually improving the quality of Baltimore's stormwater.

Before monitoring efforts began in Watershed 263 in 2004, Stack had no quantitative data to identify the scope and scale of the problem. Monitoring data from the Chesapeake Bay Program reaches only as far as the outer portion of Baltimore Harbor, where tidal water mixes and dilutes pollutant loads flowing from the outfall pipes.

Data also help Stack make the case for urban stormwater as part of the bigger landscape of Bay restoration priorities. He recently presented some of the data from Watershed 263 at the annual meeting for the Bay Tributary Strategies, roadmaps for implementing river-specific cleanup strategies for the state. Stack also testified before the state legislature in March to appeal for targeted funding for urban stormwater BMPs in the new Chesapeake Bay Trust Fund created this year.

Cherigo climbs out of the drain, strips off his grimy Tyvek suit and gloves and walks over to greet Stack, who quickly finishes typing a message and stuffs his Blackberry in the pocket of his raincoat. Data collection has been running smoothly at the Lanvale site, Cherigo reports, but nearby Baltimore Street has problems. The base flow in the storm drain at Baltimore Street is so high that the added storm flow velocity seems to be overwhelming the automated sampler. It may be necessary to alter the sampling protocol, Cherigo tells Stack.

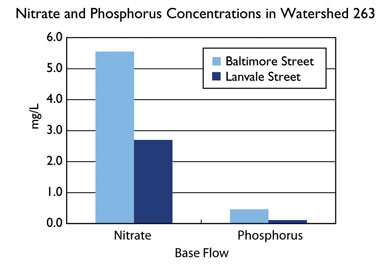

As it turns out, high base flow isn't the only irregularity in the Baltimore Street catchment area. The water quality data from this site show unusually high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus — high even for Watershed 263. Where might these nutrient loads be coming from?

Arriving at Bruce Street, a street so narrow that a single car can fill its width, Guy Hager closes and locks the car door and crosses the street. On one side of the street sneakers hang from overhead power lines in an empty lot, overgrown and full of litter. On the other side of the street metal doors barricade the opening to the Bruce Street stables. The doors stand partially ajar, framing several bright red wagons with yellow wheels.

"The Chesapeake Bay model doesn't have point-source pollution from city horse manure in its calculations."

Standing outside the stables, Hager announces his presence, identifying himself with the Parks & People Foundation. Wearing a baseball cap, he squints against the glare as he looks inside. Over the barks of a large dog tethered just inside a gate, a young man working in the outer courtyard nods at Hager and shouts to stable owner Ed Chapman to alert him that he has visitors.

Inside the stable, where ponies live in close quarters, Hager finds Chapman stooping low under the weight of a shovelful of horse manure. His small, wiry frame tenses with the effort. The pungent smells of manure and hay fill the stable, a historic building that has stood on Bruce Street for more than 150 years.

Chapman turns the shovel over an empty wheelbarrow and pushes the load toward the stable entrance, arousing a whinny of interest from a small brown pony in the corner. Steering the wheelbarrow over a makeshift ramp — a board propped over the uneven curb — he pushes into the glare of the outside courtyard. There the manure shed stands with doors open.

When the younger man starts unloading the manure from the wheelbarrow Chapman finally stops to greet Hager. They haven't seen each other for a while.

Chapman and his friends are part of a dwindling group of Baltimore "arabbers." The term "arabber" derives from British slang, "arab," used to describe people who made their living hawking on the street. Arabbers drove colorful horse-drawn carts filled with fruits and vegetables to areas underserved by grocery stores, announcing their arrival by distinctive hollers or songs. A historic way of life in Baltimore, arabbing was once common all over the East Coast, an entrepreneurial practice that dates back to the Civil War. Now it's disappeared from every city except Baltimore. The number of arabbers today hovers around a dozen. Chapman has been doing the job since he was 12, and on occasion he still drives his horse-drawn cart to sell produce in West Baltimore. At 88, he'll probably retire soon.

Back in 2006, Hager knew nothing about the Bruce Street stables. He was working across the street on a greening project when a film crew from The Wire, an HBO police drama, showed up on Bruce Street and began painting a mural of horses and cowboys on the outside of the stables. That tipped Hager off to the horses and gave him the clue that horse manure might be leaching into the catchment area's stormwater.

He discovered Chapman and other elderly stable hands had been leaving manure on the concrete pad outside the stables. When it rained, the manure washed straight through a hole into the alley adjacent to the stables. The nutrient-laden water then rushed into the storm drain and through the pipe that runs under Baltimore Street.

![[Maryland Sea Grant]](/GIFs/h_footer_mdsg.gif)