By Erica Goldman

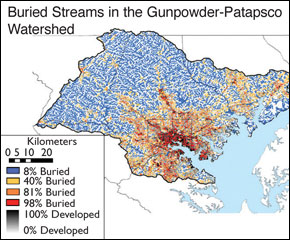

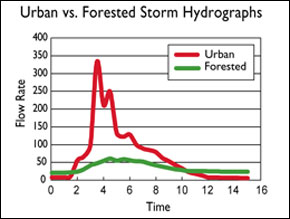

Streams go underground in increasing numbers as they move from forested areas toward urban centers like Baltimore (map above). In Watershed 263, where all the streams lie buried underground, impervious surface area tops 75 percent — which leads to high-volume, flashy stormwater flows, compared with forested areas where rain is absorbed by the ground (storm hydrograph above by Kent Belt). Photograph of the storm drain by Erica Goldman, map from Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment and storm hydrographs by Ken Belt.

|

Missing chunks of concrete leave large pockmarks in the curb at the corner of Lanvale and Stricker streets, maybe knocked loose by a car taking the turn too fast. The chipped curb leaves the stenciled red letters on the opening of the storm drain hard to read. But from the top, the words remain legible — "Trash Kills Crabs."

The banged-up corner captures the neighborhood's contradictions. It carries an environmental message, one crafted to educate the public about the connection between city storm drains and the Bay. On the other hand, as chunks of the curb came loose and fell into the street, they no doubt ended up in that very drain, sending crumbled bits of pavement laced with nutrients and heavy metals into the stormwater network.

Dirty streets make the biggest contribution to the water quality problem in Watershed 263. Streets contribute 70 to 80 percent of the total suspended solids and 30 to 40 percent of the nitrogen and phosphorus to stormwater in this watershed, according to data from the sampling effort. Most of that comes from car emissions depositing chemicals onto asphalt. Impervious street surfaces also serve up other nasty substances, such as volatile organics from fossil fuel combustion, heavy metals, and vehicle fluids like oil and antifreeze.

Bill Stack and his colleagues at the Department of Public Works are experimenting with a suite of urban Best Management Practices (BMPs) to figure out which efforts might bring the biggest benefits for water quality. This summer, the Department plans to implement six different urban BMPs in tandem, with the city of Baltimore contributing over $300,000 for this effort. Stack is particularly excited about a curb-extension greening project that will bring biofiltration capacity to the storm drains. These will help to treat stormwater before it reaches the drain and improve the aesthetic characteristics of the area, he explains.

The ongoing water quality monitoring data allow for a before-and-after comparison of the success of these practices in improving water quality. So far, street sweeping is the only BMP that has been studied in a rigorous experimental manner.

Street sweeping dates back to the 1930s and, with new technologies developed in the 1990s, it's become an effective way to prevent coarse particles of organic matter from reaching the stormwater network. This is key, Stack says, since pollutants like heavy metals tend to enter the system attached to larger particles.

An unswept street delivers 75 percent more particulate matter than one that has been swept, according to findings by graduate student Catherine DiBlasi at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. But her research also found that increasing the frequency of street sweeping has little effect on the overall concentration of contaminants in the stormwater. Baltimore should keep sweeping its streets, but that alone will not likely prove a magic bullet for the health of the city's stormwater.

![[Maryland Sea Grant]](/GIFs/h_footer_mdsg.gif)