|

Up from the Bottom: Oysters for the 21st Century

Michael W. Fincham

|

The Choptank Oyster Farm has its grow-out grounds on LeCompte Bay. Depending on the season and the market, the farm keeps 3,000 to 4,000 floats in the water, holding up to eight million oysters, including those newly spawned and those almost ready for harvest. The farm is operated by Marinetics, Inc.

Credit: Michael W. Fincham. |

"The future is different from

what it used to be."

— Maryland waterman

IF OYSTER FARMS EVER SUCCEED IN MARYLAND, AND START MAKING MONEY for farmers, they might look a lot like the Choptank Oyster Company, a farm that is already growing oysters and already making money for itself and a name for its products.

Driving west out of Cambridge, Maryland, you head past the gas station, the old shotgun cottages, and the new townhouses out in the fields along the edge of town. Take the left fork at Long's Store with its shuttered gas pump and keep heading west into the country. At Castle Haven Road, take a right and drive past the long swatches of loblolly pine broken by farm fields and patches of marsh and glimpses of the river. Drive all the way to the end, and then keep going past the stone gateway, past the fields planted with corn and soybeans, past the potholes in the dirt-packed road until you hit the water and the long pier and see spread out on both sides of the pier thousands of floating rafts, thousands of white-ringed rectangles holding dark green bags of oysters. You may have found the future of oyster farming in Maryland.

At least you've found one version of the future and one that seems to be working already. Kevin McClaren first drove down those roads, dodging potholes, in 1999, and as manager for the new company began building an oyster hatchery in a barn. The company didn't put its first oysters in the water until 2001 and didn't sell one until 2004, according to McClaren, who used to run fish farms in the hills of western Massachusetts before migrating to the water-soaked flatlands of Dorchester County. He's stocky, brown-haired, energetic and opinionated — hardly a rarity in the oyster business. The company, says McClaren, recently began making profit.

The first key to their success was the start-up funding and long-range investment plan worked out by the husband and wife owners, Robert Maze and Laurie Landau. A second key was the site McClaren found: he grows oysters along a gently curving beach out on the hook of land where LeCompte Bay meets the mainstem of the Choptank River, a spot where the ferry once offloaded visitors from Talbot County and points north. When McClaren came down from the north, he looked for a beach that had a good flow of water but was far from sewage plants or multiple septic systems or large animal operations. A third key to his success is the way he grows his oysters: up from the bottom in floating racks where the oysters enjoy a river flow that brings water rich in oxygen and in the algal food they like.

ONLY FIVE COMPANIES ARE listed as currently growing and selling oysters in Maryland's Chesapeake Bay, and all use some of form of off-bottom farming, either cages or more commonly floats, a technique that Max Chambers was using on the Nanticoke River some thirty years ago and Frank Wilde was trying on the West River. Most Maryland oyster farmers, however, grew their crop along the bottom in decades past — if they were lucky enough to get some bottom to lease in a state that did not encourage oyster farming. They usually had to prepare their leased grounds by first putting down shell as a firm substrate before planting seed oysters on top, seed that had to be hauled in from elsewhere. Most of those farms in Maryland, both off-bottom and on-bottom, were wiped out during the 1980s when droughts sparked epidemics of two oyster diseases, MSX and Dermo. By 1993 the Baywide Chesapeake oyster harvest — from farming and fishing — had hit its historic bottom.

Neither disease has disappeared yet, but oyster farming may be ready for revival now after a recent series of historic decisions.

|

|

|

|

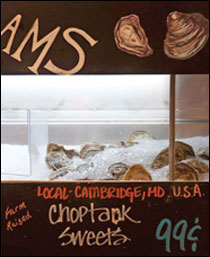

The WholeFoods Market in Annapolis (right) sells Choptank Sweets and Choptank Salts for 99 cents an oyster, shucked or unshucked. Kevin McClaren (left) promotes the local appeal of Choptank oysters, marketing heavily in the Baltimore and Washington area. "People are nostalgic for what's theirs," he told Chesapeake Bay Magazine. After working for fish farms in Massachusetts, he apparently hasn't yet transferred his own nostalgia from the Boston Red Sox to the Orioles or the Nationals.

Credit: Michael W. Fincham. |

Last year the Governor of Maryland put forward a new oyster aquaculture bill that removed many of the roadblocks that hampered oyster farming for more than 100 years. Influenced over the decades by politically savvy watermen who opposed private oyster farming, previous legislation set up restrictions on lease sizes and locations, and on non-resident and corporate ownership. Following up on last year's aquaculture bill, in May the state of Maryland opened 600,000 acres for future private farm leases, which can be held by corporations and nonresidents. The state also converted 25 percent of the viable public fishing grounds into oyster sanctuaries and stepped up its campaign against poachers.

The new changes in the law set phones ringing this spring in a number of state agencies, including the Department of Agriculture, which helps aquaculture businesses with permitting and regulation. The kind of oyster farming that is beginning to emerge in Maryland could be a mix that includes both on-bottom and off-bottom aquaculture, according to Don Webster (see Commercial Oyster Aquaculture Resources above in the right column), Maryland Sea Grant Regional Aquaculture Specialist and past chair of the Aquaculture Coordinating Council. On-bottom farms would mostly produce oysters for shucking and off-bottom farms would turn out single oysters designed for the pricier half-shell trade. The mix of farmers could include newcomers like McClaren, established seafood businesses looking for new supplies, and watermen who want to try another way of working the water.

For wannabe farmers, the roadblocks are down, but plenty of potholes remain, including bureaucratic delays, permits, surveys, start-up costs, disease risks, and turnaround time. For watermen who would be farmers, the potholes can look like craters. After spending their work lives as solitary entrepreneurs, most watermen are not in a position to invest heavily in shell and seed and new gear, and then wait three years before harvesting.

"They don't have it, they can't borrow it, and they don't have any cans of money buried in the backyard to dig up," says Tommy Zinn, president of the Calvert County Waterman's Association. He puts the number of watermen who would try farming at fewer than one in twenty. Zinn thinks that one alternative could be a cooperative venture that shares the cost, the work, the risk, and the rewards. With a small group of local watermen, Zinn has begun experimenting with this option by planting 10 million baby oysters along the bottom of a creek off the Patuxent River.

Forty miles down the road from the profitable floats of the Choptank Oyster Company, down at the marshy tail end of Dorchester County, a group calling itself the Waterman's Trust is designing a different business option, an oyster farm on Fishing Bay that will hire watermen as farm hands. The start-up funding and the business savvy for the farm comes from the Waterman's Seafood Company, a small corporation run by two accountants that operates a profitable restaurant in Ocean City and recently partnered with waterman Jay Robinson to open a small seafood plant in the county. Their farm will focus on traditional bottom planting of spat on shell, but is hoping to try out triploids, the sterile, fast-growing oyster that many Virginia growers are using.

One of the goals of the Trust is "preserving the waterman's way of life," and the labor force for the new farm will come from dozens of watermen who live and work around a number of down-county fishing villages. Watermen would still work their own boats as individual contractors, but they would be keeping their boats at the company dock and working oysters off the company's leases. The work will be more than harvesting: it could include tasks like putting oyster larvae in setting tanks, planting spat on shell, washing oysters, and checking the grounds for disease and predation and poaching by other watermen. The way of life may stay the same, but the work will change. "It's going to be a different animal altogether," says Ryan Bergey, one of the founding partners.

The farm will be located next to Crocheron, a tiny town surrounded by huge swaths of wide, flat water where Fishing Bay and the Nanticoke, Honga, and Wicomico rivers all flow into and merge with the mainstem of the Chesapeake. Watermen have hunted this open range for wild oysters and crabs and fish for nearly two centuries, often with little concern for laws and leases, a history which has the owners of the new farm nervous about poaching. "It's key to have it real close," says Bergey. "So when we have harvestable oysters available for theft, we will have somebody there watching the radar." The person watching the radar would, most likely, be a waterman.

Eighty miles down the road from the Choptank farm, down in Crisfield, the oyster capital of the world during the late 19th century, Casey Todd is setting up a more traditional farm. It will be large scale — with 400 to 500 acres — but will operate essentially as an add-on to his existing business, Metompkin Bay Seafood, a company that has a track record of success and operates one of the state's last remaining shucking houses. For starters that gives him plenty of shell for preparing oyster bottom and for setting new oysters — and plenty of workers for shucking them. Operations like his have survived the Chesapeake's seafood declines by importing oysters from the Gulf Coast as well as crabmeat and soft crabs from Asia. His company currently employs 30 to 40 people, depending on the season, and the oyster farm, he says, could add 10 to 20 jobs to his payroll — if it succeeds.

Success is the big "if" in an estuary where MSX and Dermo still kill oysters in large numbers. Casey planted an oyster farm before, back in the 1980s, and saw his oysters all die from disease, an experience that tempers his hopes for his new farm. "This is the oyster business," he says. "I'm not an optimist. Just when you think you're doing well, an oil tidal wave comes over the horizon and wipes out your beds. Or a bunch of cownose rays comes in and munches them all up." He clearly has enough optimism, however, to try again.

The new hopes for oyster farming stem, in part, from lessons learned from earlier failures. The future, unlike the past, would be built around oyster seed created in hatcheries rather than around wild seed hauled in from elsewhere, a technique that helped spread disease around the estuary. Oyster larvae spawned in hatcheries are disease free, and selected strains can be crossbred for disease resistance and fast growth (see Survivor: Chesapeake). Farming around disease requires new tools like these as well as new oysters like the triploid oyster, an invented, sterile species that carries three sets of chromosomes (see Trials & Errors & Triploids). This genetic redesign of an ancient oyster creates one that is fatter and can be sold year-round. Its biggest benefit may be fast growth. One key lesson seems to be: the best way to beat disease is to grow oysters fast and harvest them quickly.

Another lesson might be: the best way to grow oysters fast is to grow them off the bottom. That, at least, is one of the lessons offered by Kevin McClaren, the energetic manager of The Choptank Oyster Company. The start-up costs for off-bottom are higher because of all the extra gear, but the oysters grow faster than they do on the bottom, and the final product, a fresh oyster on the half shell trade, brings a much higher price than a shucked oyster in a can. Is the future in off-bottom or on-bottom aquaculture? It's probably in both. For newcomers like McClaren and old hands like Casey Todd, the tradeoffs are tricky and the debate will still be in session a decade from now.

For now the Choptank Oyster Company with its floats full of oysters has traveled farther along the road to profit than other farms in the state, and the largest lesson in their success might lie in the marketing savvy and street hustle that McClaren has shown. He named his core product "Choptank Sweets," creating a catchy brand name that tells oyster eaters where the flavor's coming from. Oyster connoisseurs — like their cousins in wine criticism — love to evaluate the terroir of an oyster, that's the French term for the combination of land and water and weather and husbandry that create the unique flavor of a brand. "Wellfleets" and "Island Creeks," to cite two examples, now mean a Cape Cod Bay flavor, just as "Blue Points" once upon a time meant a flavor from the briny South Bay of Long Island Sound. "Choptank Sweets," according to various critics, means an oyster that is plump and sweet with a creamy texture and even a hint of burnt mineral.

McClaren also sells "Choptank Salts," a selection that has spent time soaking in Chincoteague Bay. Once he had oysters he could harvest and brands he could market, McClaren started singing their praises, getting his oysters into regional magazines and high-end restaurants and big-time retail outlets like Whole Foods.

For those just starting down the same road McClaren is willing to offer some cautions. "There are a lot of potholes," he says, perhaps trying to scare away competitors, "a lot of ways to screw it up." Growing oysters includes conditioning the brood stock, getting them to spawn and set, then grading and culling, cleaning and packing and shipping. All these steps have their missteps and most of the work has to go on through the heat of summer and the ice of January and the winds of March.

And all this work, he warns, is only 50 percent of the job. "The other 50 percent is getting out and hitting the streets and selling those oysters and making money off them," he says. "There's a lot of difference between the two."

|

|