Unloading crabs trucked in from BWI Airport, where they arrived from the Gulf of Mexico, Art Oertel continues the long tradition of providing quality seafood to cusomers on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Photograph by Skip Brown.

Contents

Sharpening the Crab's Competitive Edge

Safe Seafood in the Chesapeake Bay

By Jack Greer

Karen Oertel walks along the wintry edge of Kent Narrows, a slash of slate gray that runs between Kent Island and Maryland's Eastern Shore. She glances toward the Route 50 bridge and at the marinas and pleasure boats that now line the Narrows. There's not much room here for traditional seafood processors anymore.

Arriving at an unassuming white shed, she steps inside, parting heavy plastic strips, like those that might mark a supermarket food locker. Here, amid the sounds of oyster shucking, the Chesapeake seafood industry seems very much alive.

Oertel ducks to avoid the metal cages that creak around the ceiling on a track, like miniature coal cars. The cages deliver a steady stream of oysters from the loading room. When tilted, they spill their white coal onto the table with a clatter. She circles around a group of large metal tables, where two rows of oyster shuckers wearing big yellow rubber gloves face each other across piles of shell. As she inspects the work she stands out in her red jacket, covered by a white windbreaker.

The tables take up the whole center of the tight room. It's loud. This is Harris Seafood, in February, after a fresh shipment of oysters has arrived from Pamlico Sound in North Carolina, along with some oysters from Deal Island down the Bay. The shuckers — almost three dozen of them — are a miracle of movement. They first jab each oyster against an electric grinder to knock off a spot on the shell. Then they use a short shucking knife to pry open the shell and slice the adductor muscle. The oyster slips out and into a pail. The shuckers get paid a dollar a pound and can make $20 an hour. This is piecework. Move on.

There are men and women here of every hue. Above the noise one friendly woman, African American, says there used to be more money in shucking oysters. Now business is down. She only does this sometimes — other times she drives a school bus.

Talking is difficult, and most focus on their work, casting quick glances around at the mayhem. When conversation does come, it may be in Spanish. More than a third of these workers hail from Mexico. Everyone is working like crazy. One man rocks from foot to foot as though hearing music in his head. Oertel says that sometimes they play the radio — loud — and then you can hardly talk at all. It used to be hymns.

And the oysters all used to be from the Chesapeake.

While cash crops like tobacco first fueled the Chesapeake's growing economy, another harvest sprang up that did not require large capital investment and did not depend on owning large stretches of land. This was the Chesapeake seafood business, and it proved the lifeblood for many Bayside settlements. Up any good-sized creek or cove a traveler would find watermen's workboats, crab shedding floats, oyster shucking houses. Some eked out a living along the shore, others launched full-fledged seafood businesses and prospered. Either way, those who harvested, processed, and sold Chesapeake seafood shaped a rich waterside culture soon known around the country. They passed on a heritage of sleek workboats, weather-toughened watermen, and legends of bountiful fish and shellfish. That heritage is now threatened by dwindling stocks, labor shortages, and global competition.

Most of all, it's threatened by the ecological decline of the Bay itself. This is the theme struck most often by Oertel, who's become a prominent voice for the Bay's traditional seafood industry.

The morning Karen Oertel came into the world, in November 1946, her father harvested 78 bushels of oysters near the mouth of the Corsica River on Maryland's Eastern Shore. That's the story told by her husband, Art Oertel, now sixty-five, and the historian in the family. Her life, it seems, was bound to oysters from the start.

Together Art and Karen Oertel, along with her brother and sister-in-law, Jerry and Pat Harris, have built a life on oyster shells — and now on crabs and other seafood as well.

Oertel says they could have sold out to condos a long time ago. But they didn't. "We're in this for the long run," she says.

With her sharp brown eyes and quick wit, she soon became a spokesperson for the family business and eventually for the local seafood industry. She's served on advisory committees, councils, task forces, and chambers of commerce. Now she's on the Board of Directors of the Maryland Agricultural and Resource-Based Industry Development Corporation (MARBIDCO), created in 2004 by Maryland's General Assembly to give the state's farming, forestry, and seafood industries an economic boost.

It has not been an easy path. The Bay has seen sharp declines in oysters since her father, W.H. Harris, first launched his seafood business back in 1947, after he returned from serving overseas. That year Maryland's oyster harvest came in around 2 million bushels a year. Though it saw some ups and downs, thirty-five years later the catch was still hovering around 2 million bushels. It must have seemed that the oysters would go on forever.

Then, in the mid-1980s, two oyster diseases, MSX and Dermo, rode a drought-driven salt wedge well into Maryland waters. They soon decimated oyster bars in the northern Bay, as they had in Virginia. The harvest plummeted, reaching rock bottom in 2004, with a commercial haul of less than 7,000 bushels.

All through this time, the Harris-Oertel clan worked to keep their seafood business going. They now run a seafood restaurant that sits right next to the oyster shucking plant. Seated around a cozy table there, they recall the heyday of the oyster business.

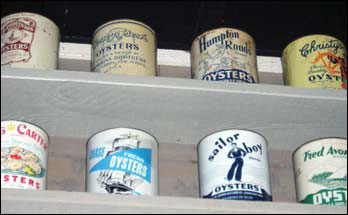

Art Oertel points along the walls of the restaurant, where two rows of shelves hold a collection of oyster packing cans. Their labels sport all manner of graphic designs and names. There's Jack's Oysters, Sailor Boy, and Silver Sea. There's Tred Avon River and J.C. Lore.

The best lithographs grace cans from about 1900 to 1920, he says. The companies could afford to pay for them — the oyster canning business was booming.

Back before World War II, Karen Oertel's uncle told him, a local company, A.C. Harris, shucked 1,900 gallons of oysters in a single day. The shuckers went to work at midnight, he says, and didn't stop until 4 o'clock that afternoon.

Around Kent Island alone, he figures there were some two dozen packing houses. Oscar Dunn, Brown Brothers, Calvert Jones, Alec Thomas, Harvey Ruth, Kneeland Shellfish, Diggs Seafood, John Coursey, B & S Fisheries, and many others. There was also A.C. Harris, Holton Harris (Karen Oertel's grandfather, who owned Kent Oyster Company), and W.H. Harris.

More than 650 old oyster cans fill Oertel's collection, tin ghosts of hundreds of oyster companies — companies that have all faded away. Or almost all.

One by one the packers around Kent Narrows closed, he says, until there were only two. B & S Fisheries and W.H. Harris. About four years ago, Jean Stelmach, the owner of B & S, closed up shop. That left W.H. Harris, now operating as Harris Seafood, as the last full-time oyster shucking plant in the Narrows and — according to Art Oertel — in the entire state of Maryland.

Whether counting on oysters or fish or crabs, so many of the seafood businesses that supported Bayside communities from Kent Island, Maryland to Hampton, Virginia, have slipped away.

A sad irony, since all around the country the seafood business is booming.

![[Maryland Sea Grant]](/GIFs/h_footer_mdsg.gif)