|

Before the Next Flood:

Contending with Climate Change on Maryland's Eastern Shore

Erica Goldman

Up and out of the floodplain, one painstaking inch at a time. Harriett and Bud Hankins added an additional four feet to the height of their house when they rebuilt after the devastating flooding of Hurricane Isabel. The process took nearly a year to complete.

Credit: Harriett and Bud Hankins.

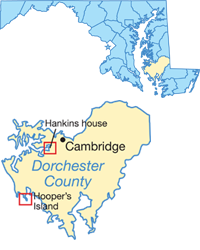

NICK LYONS REMEMBERS when tomatoes grew in southern Dorchester County, when bustling canning operations and crab plants made Crapo and Hogsville prosperous, back before farm fields and pastures became marshes.

He's seen the waters rise since then — freak floods that are no longer freak, normal high tides pushing higher and higher.

For more than 20 years, Lyons has served in the county's executive office — he's currently the codes administrator and floodplain manager, charged with inspecting properties and granting permits for new construction and structural renovations. For decades, he's given the same advice to homeowners that come to his office seeking permits. "Whatever you do, elevate your house out of the floodplain."

Since the 1990s, Lyons has argued that "freeboard" be incorporated into the county's building codes. Freeboard is a factor of safety, an increment of elevation above the base flood elevation, that can better protect against wave action, land subsidence, or sea level rise.

Legislation to incorporate freeboard has been introduced three times in the Dorchester County Council since the early 1990s — and three times it's been defeated. The bills have been voted down because of concerns over increased building costs, according to Lyons, who believes this concern is ill founded. He says the cost increases would likely never exceed one percent of the cost of the house. And incorporating freeboard could also lead to a large discount on federal flood insurance through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), around 20 percent, Lyons explains. "The investment is priceless, in all honesty."

But freeboard has been a tough sell in Dorchester County.

This evening the council will conduct a public hearing on freeboard legislation, newly introduced in September. Lyons is optimistic. Bill 2010-20 would amend the Dorchester County Code (Section 155-37) by requiring all new construction and any substantial improvements to residential and commercial structures to elevate the lowest floor to a flood protection elevation that would incorporate a three-foot freeboard.

Lyons will be presenting the bill at the hearing. "I am going to try my best to get this through tonight," he says. "It will be a good thing for the county. Whether they see this yet remains to be seen."

He hopes the political climate for passing freeboard legislation finally may be right in Dorchester County. This is the first time a freeboard bill has come up since Hurricane Isabel inundated the county in Fall 2003. Hundreds of houses in the county were damaged by the storm and flooding caused by the storm surge. While some have since been elevated and rebuilt, many others have been abandoned.

"I think I'll get it this time," he says. "Isabel will be my saving grace."

Lifting Up from the Flood Waters

Hurricane Isabel delivered over a foot of water to the house of Harriett and Bud Hankins. Located at the head of Fishing Creek, parallel to the Little Choptank River, the house was built in the late 1600s or early 1700s — a new foundation was constructed in the 1940s, though it still sat flat on the ground. When the Hankinses bought the house as their retirement home in 1985, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers erected a bulkhead on one side of the property and put riprap in along the other — covering some 365 feet of waterfront. The Corps was worried about wave action and wear on the property because of its position at the head of the creek. Nobody said anything about elevating the house.

Climate change and sea level rise drive and exacerbate coastal hazards along Maryland's 3,000 miles of coastline. more . . .

Even when the Hankinses renovated their property in 1991, they heard no concerns about elevating the house, which is set back more than 30 feet from the shore. No one ever remembered water coming in.

Hurricane Isabel was another story. The water came and went quickly, according to Harriett Hankins, but left a big mark. The house flooded knee deep — after the waters receded, she and Bud began ripping sodden drywall from the sunroom. Black mold moved in immediately. They left the walls open to dry out.

Over the next week or so, the Hankinses brought in contractors who advised them not to do anything in a hurry, but to take time to dry it out completely. Many times, they were told, wood floors will go back into place. The contractors set up giant blowers near the foundation, while the Hankinses scrubbed the kitchen with the Clorox solution recommended by FEMA. Then they left to visit their son in Kenya and spend a couple of months on the island of Lamu. While their house back in Cambridge was drying out, they were deciding whether to rebuild.

They knew the future would bring even more flooding to Maryland's Eastern Shore. A retired schoolteacher, Harriett Hankins, 81, serves as a citizen representative to the Coastal and Watershed Resources Advisory Committee (CWRAC), an independent advisory body to the Secretary of Natural Resources and to Maryland's Chesapeake and Coastal Program — just one of several volunteer organizations she engages in. She's keenly aware of the regional predictions for sea level rise and inundation — and what these predictions are likely to mean for Dorchester County.

Projections forecast over a foot of sea level rise in the next 50 years. Closer to three feet in the next century, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — that, is if CO2 emissions continue at their current high rate (see Sea Level Rise in the Bay). In Dorchester County, some 25,000 acres of forest (nearly 40 square miles) and 60,000 acres of wetlands (more than 90 square miles) could be lost by 2050, according to a recent scientific study done at Towson University. Rising water will also intensify coastal flood and storm surge events. A one-foot rise in sea level translates to a one-foot rise in flood level. Hurricane Isabel already brought a 6-to-8-foot storm surge. Overlay sea level rise on top of warming impacts and houses on the coast grow more vulnerable each year.

Where Land and Water Meet

When the Hankinses returned from Kenya, they found that the damage to their house, although extensive, could have been much worse — the wood floors had indeed moved back into place. They decided to rebuild and to elevate above the minimum required by FEMA and the state of Maryland.

Hurricane Isabel left a mixed legacy on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Dorchester County residents Harriett and Bud Hankins were able to rebuild and elevate their house within a year or two. Others, in the low- lying areas of Hooper’s Island, abandoned their houses or are just now rebuilding seven years later. more . . . Hurricane Isabel left a mixed legacy on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Dorchester County residents Harriett and Bud Hankins were able to rebuild and elevate their house within a year or two. Others, in the low- lying areas of Hooper’s Island, abandoned their houses or are just now rebuilding seven years later. more . . .

After Hurricane Isabel, FEMA required houses that sustained more than 50 percent damage to be raised above base flood elevation or they would not be eligible for flood insurance. And flood insurance is a necessity for houses located in a floodplain — federally backed mortgage companies will not issue loans for houses without flood insurance.

Elevating the Hankins house would prove no small feat (see photos at end of the article) and would take nearly a year. The age of the house precluded using heavy equipment to dig out the foundation, so contractors dug it out by hand until they could slide I-beams underneath to raise it up, one painstaking inch at a time. Then they brought in a sand-loam fill to make up the necessary height. The Hankinses chose to elevate their house by four feet. Essentially, they incorporated a voluntary two-foot freeboard, which corresponds with recommendations in Maryland's model floodplain ordinance.

The state of Maryland offered significant financial assistance to help county residents with construction costs, while mortgage companies offered very low rates. Still, for many, the costs were too high, and they abandoned their houses outright. To finance the rebuilding of their house, the Hankinses sold another property. They count themselves among the lucky ones.

How well are communities along the low-lying Eastern Shore readying for future storms with the power of Isabel? To answer this question, anthropologist Michael Paolisso and industrial economist Matthias Ruth have been studying coastal communities, among them, the community of Smithville in Dorchester County, roughly 13 miles southwest of the Hankins house. In this study, the University of Maryland researchers are exploring issues related to climate change and environmental justice in underrepresented groups.

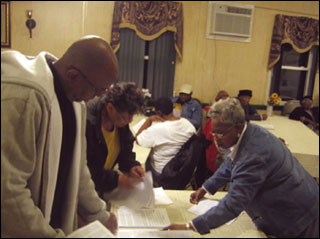

Paolisso recruited members of the New Revived United Methodist Church to participate in a series of three workshops. Working with this small, African American congregation, Paolisso hoped to gauge their perceptions about climate change as it relates to their community. He began by asking participants to think about what words they associate with climate change and how those words relate to each other. He also provided maps with projections for sea level rise and coastal flooding that included Smithville and the church.

The participants were well experienced with heavy storms and floods, Paolisso found. They knew which areas are high and whose houses were likely to flood, and they had a sense for which roads might be cut off and which members of their community might need assistance.

But their concerns were on the here and now, not the future. Residents were interested in the maps showing projections for sea level rise and future flooding, but they never showed a sense of urgency, Paolisso says. "On the surface, I didn't get a strong reaction of, 'we're in trouble.' I didn't find them thinking 10 to 20 years out."

In the four communities that Paolisso and Ruth have studied, including two in Massachusetts, nobody talked specifically about adapting to climate change. Most people have a perception, says Paolisso, that climate change and sea level rise are in the future and there's not much that can be done about it anyway. "I don't think people are thinking about how they or their community can adapt to climate change. Many of them have more pressing needs."

Are residents worried about predictions for rising waters and coastal floods? In Smithville, anthropologist Michael Paolisso worked with members of the New Revived United Methodist Church (above) to gauge their perceptions and attitudes about climate change.

Seven miles south, Smithville Road becomes Hooper's Island Road, eventually running between pools of water and marshes dotted with the charred-looking skeletons of evergreen trees — these trees were killed by saltwater intruding inland, driven by higher than normal tides and storm surges. The road descends and flattens out then arches high across the bridge leading away from the mainland.

More than a bridge and a road connect Hooper's Island with Smithville. Here too residents living on the low lip of the Bay seem not to worry much about future sea level rise.

On Hooper's Island, home to approximately 420 residents — many of them watermen and their families — Hurricane Isabel left a mixed legacy. Some were able to rebuild quickly, elevating their houses in the process. Roughly one-third now sport new cinderblock foundations and sit a few feet higher than before. Others are only now rebuilding and elevating their houses, more than seven years after the storm — construction sites abuzz with activity punctuate quiet streets. Meanwhile, dozens of other houses stand abandoned — paint peeling, black mold encrusting white shingles. On one side of the road, a streetlamp stands in water several feet deep. Next to it, a rusted-out metal shed. Up the road on the other side, trees and shrubs invade the facade of another house, weaving through the walls and windows an organic message of "Keep Out" to anyone who draws near.

Hooper's Island still houses two crab processing plants — Ruark's and Phillips. Jay Newcomb, who manages the Phillips plant, has lived on Hooper's Island all his life. He's currently serving his second term as Dorchester County Commissioner and also operates Old Salty's, a restaurant on the island that among much else serves outstanding lump crab cakes.

Newcomb relates to the struggles that people face on Hooper's Island. He knows that many cannot afford to rebuild or elevate their homes. Many own their houses outright and do not have federal flood insurance. For them, as sea level rises, abandoning the island ultimately may prove their only option. In terms of storms like Hurricane Isabel, he says that his constituents do not feel a strong sense of urgency. Most feel that Isabel was an unlucky chance event, he says, not a harbinger of worse things to come. The community is not yet thinking too much about how to adapt to changing climate conditions — how to prepare for more intense storms and rising waters. Life unfolds here one day at a time.

Planning for Rising Seas

If so few residents identify sea level rise and more intense storms as a growing risk, how can the state of Maryland help communities prepare for the future? For some time now, a number of state agencies have been working with county and local officials to incorporate the impacts of climate change in master plans of community development.

Gwen Shaughnessy, a coastal hazards and climate program specialist for the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), has helped develop the Coast-Smart Communities Initiative, a NOAA-funded program aimed at helping coastal communities plan for and adapt to climate change. The program is a direct response to recommendations in the Maryland Climate Action Plan, released in 2008 (see For More Information).

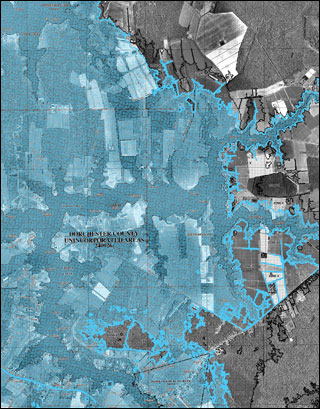

Shaughnessy's efforts take a two-pronged approach. First, a technical mapping component helps pinpoint those areas most at risk — this process incorporates data on coastal topography and combines them with projections for sea level rise and storm surges. She then works directly with local governments to incorporate this information into the development planning.

The idea, says Shaughnessy, is that planning for climate change should not be separate from the overall planning process, but a practice of fitting it in to day-to-day business. "Local governments are charged every day with deciding where to develop, where to grow. We're trying to help them integrate into this planning the potential changes that climate change might bring."

Raising structures such as houses, utilities, and roads above the base flood elevation (freeboard) is a significant starting point, says Shaughnessy. Such practices build in a buffer, a factor of safety, especially because the projections of climate change are just that — projections. "It is difficult to draw a line in the sand and say that this is where the extent of the flooding is going to occur. So we are asking local governments to go above and beyond what is required."

Shaughnessy acknowledges that this is a tough sell — local governments already are contending with a number of environmental regulations, such as the new requirements for compliance with Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) requirements to limit specific pollutant discharges by watershed.

One key is to recognize where opportunity fits without becoming an extra burden, says Shaughnessy. With funding opportunities through the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA), counties can apply for assistance to integrate climate change into the planning process. The town of Queen Anne on Maryland's Eastern Shore, for example, received assistance from the CZMA grant program (Section 309) to help complete their Water Resources Element. The Water Resources Element requires counties to analyze current water supplies, wastewater treatment capacity, and point and non-point source pollutants as part of their master plans. The town of Queen Anne will pioneer an attempt to integrate climate change planning into the process. The effort will include an examination of sea level rise and storm surge inundation to direct future growth out of high-risk coastal areas, as well as an assessment of climate change impacts on expected water resource demands and wastewater treatment and distribution.

Redrawing the Maps

Planning for the next great flood may soon gain new urgency for Maryland's coastal communities. For the past several years, the state, in conjunction with FEMA, has been systematically updating Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs). This effort is part of a nationwide initiative to complete a digital conversion of existing floodplain maps, explains Dave Guignet, the state coordinator for the National Flood Insurance Program. The new digital maps will be compatible with GIS (Geographic Information Systems) and greatly improve spatial accuracy for planning, permitting, and insurance applications.

But most states are still relying on flood elevation data from 1988 to complete the digital conversions. Maryland is out ahead, explains Guignet, in simultaneously upgrading the elevation maps as part of the digitization process — an effort that has generated new studies covering more than 3000 miles — inland and coastal. These studies use the optical sensing technology LIDAR (which relies on laser pulses to find range information of a distant target) to create high-resolution digital elevation maps. Updated data also account for rainfall, sea level rise, and erosion that have occurred in the past 20 years. They will not include any projections for future sea level rise, although these are planned for the future.

The Digital Flood Insurance Rate Maps (DFIRMs) are used to determine whether or not a homeowner resides in the 100-year floodplain, which then sets the availability and rate for federal flood insurance by FEMA. So far, the digital upgrades have been completed for inland areas in Maryland. The coastal maps for counties such as Dorchester are due to be released in 2012. They will likely reveal that the newly defined floodplain for the county will cover even more real estate — in a region where 60 percent of its residents are already living in a floodplain. More homeowners will find themselves facing high insurance rates or becoming ineligible altogether. That is without any accounting for sea level rise, which FEMA has funds to begin working on in the next two to three years.

"What do people do who find themselves in the newly defined floodplain? What does it mean for them and their house? We've never had to go through something like this as a society," says DNR's Shaughnessy.

The pending change in floodplain maps raises the stakes for Maryland's coastal communities. Thousands of homeowners may soon find themselves facing a choice with their own properties. The economic and social consequences could prove immense.

Standing before the Dorchester County Council at their October 19 meeting, Nick Lyons presents Bill 2010-20. He tells them that a three-foot factor of safety (freeboard) would have likely prevented a lot of the flood damage that county residents suffered during Hurricane Isabel. And in the past year, there have already been several days when the southern part of the county has experienced flooding, with floodwaters entering homes, according to Wayne Robinson, the emergency management director for county.

Lyons also tells the Council and public attendees that adopting freeboard would reduce flood insurance rates significantly — by up to 20 percent. And this cost savings would likely offset the added costs in construction. Bud Hankins is there to validate Lyons's statement about insurance rates. After having their house elevated, he says, they received a discount on their flood insurance. If the bill passes, Lyons adds, the Hankinses should receive yet another drop in their rates.

But the skeptics haven't been won over. County resident John Battista is worried about increasing the restrictions already placed on the use of resident-owned property. He would rather "risk the odds" than raise his home above base elevation. Property owners should be allowed to decide for themselves how much flood risk they are willing to take, he says.

Concerns also arise over increasing construction costs. Councilman William Nichols from District 2 argues that imposing a freeboard requirement would place too harsh an economic burden on residents. He suspects that the end result may be an increase in building costs that will negate the insurance rate decrease. "In the current economic climate," he says, "implementing a freeboard requirement will only burden a new homeowner."

Digital Flood Insurance Rate Maps (DFIRMs), such as this one for a subsection of Dorchester County, represent digitally converted flood insurance rates maps that are compatible with GIS (Geographic Information Systems). The state of Maryland, in conjunction with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), is in the process of systematically updating Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) for communities. The new maps, due out in 2012, will improve spatial accuracy and also include updated flood elevation data. Although DFIRMs currently do not include any projections for sea level rise, this is planned for the future.

Credit: State of Maryland.

Councilman Ricky Travers from District 3 and Councilman Rick Price from District 4 agree. Travers also echoes the sentiment expressed by Battista that the decision to elevate their home should be a personal one.

The time comes for a roll call vote. Four Council members opposed, only one in favor. The Council agrees not to proceed with Bill 2010-20.

Freeboard will not come to Dorchester County — at least not now. Nick Lyons is surprised and disappointed. This is the fourth time he's pushed for freeboard legislation before the County Council. This is the fourth time it has failed. He doubts that it will come up again during his tenure with the county and he's "pretty much out of steam on it."

A large number of houses already require flood insurance in Dorchester County, Lyons says. And that number will likely grow larger with the pending adoption of elevation upgrades in the new Digital Flood Insurance Rate Maps. Without freeboard, flood insurance premiums will remain high. In the end, the decision not to adopt freeboard could end up costing the homeowners of Dorchester County a lot of money.

Lyons suspects it will take another great storm like Isabel to stir up enough concern, to make people wish that they'd adopted the change when they'd had the chance. He hopes that a group of individuals will come together to bring momentum to this issue again for Dorchester County. And before it is too late.

|