Solving a Problem Like Nutria

by Phillip Hesser and Rona Kobell

The dogs are out, training to look for something no one wants them to find.

In a field at Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, Bradie, a Labrador retriever mix, and her human handler, Trevor Michaels, are playing a strange game of fetch. Michaels, an acting supervisor for the Chesapeake Bay Nutria Eradication Project (CBNEP), commands Bradie to “find it,” sending the dog searching for nutria scat he’d planted earlier. When she does, he verifies her find with a “Good girl!” and throws her a tennis ball.

These exercises are the late stages of what may be a continuous monitoring project to rid Maryland’s Eastern Shore of nutria (Myocastor coypus), an invasive South American rodent that has grazed its way through delicate marsh habitat since it arrived here over 80 years ago. With much of the work already done through intensive trapping, monitoring, and even “Judas nutria” sent in to reveal the location of others, the dogs are seeking traces of whatever nutria might be left behind. It doesn’t take many of these prolific breeders to bring numbers back up; on just one 10,000-acre parcel in Maryland’s Dorchester County, the nutria population climbed from 150 in 1968 to more than 35,000 by the early 2000s.

Smaller than a beaver but larger than a muskrat, with orange buck teeth and webbed feet, nutria are strong swimmers and live in colonies, where the females reproduce copiously. They are believed to live up to six years in the wild, a lifespan during which they can destroy plenty of marsh, which they do as they feed. Their genus name comes from two Greek words: “mys,” which translates to “mouse,” and “kastor,” which means beaver. These “mouse beavers” are also sometimes called “swamp rats,” in part because their tails are round and rat-like, with very little hair.

Margaret “Marnie” Pepper, a district supervisor and wildlife biologist for the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Wildlife Services Division who has been leading the detector dog program, said while nutria may look menacing, they’re more a case of an animal in the wrong place.

“They’re very interesting creatures,” she said. “They’re just not where they should be.”

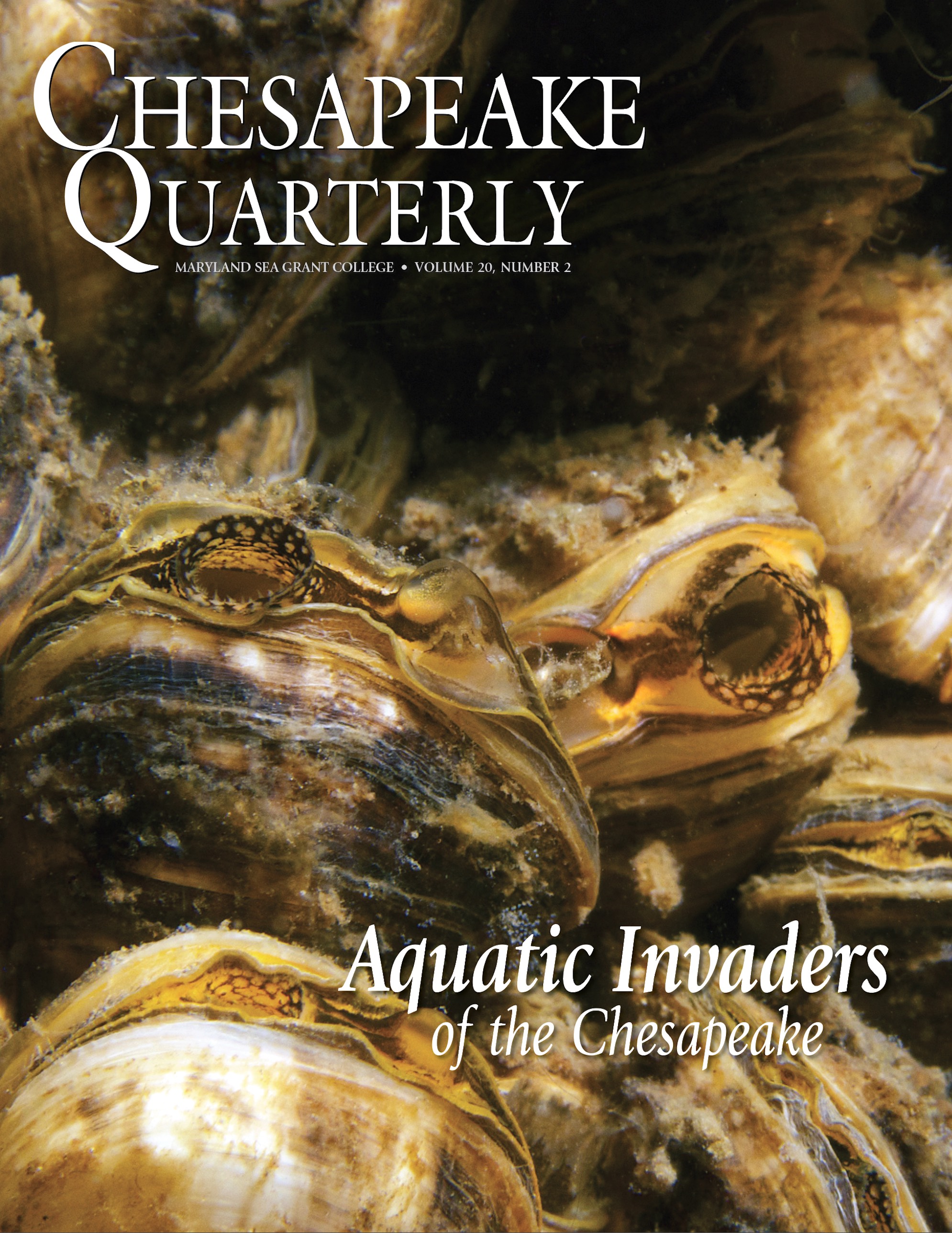

These semi-aquatic rodents are just one of many invasive animals and plants that affect the Chesapeake Bay and other watersheds, species that cause billions of dollars of damage to infrastructure projects and ecosystems every year. Zebra mussels clog discharge pipes in the Great Lakes and can be spread via recreational boats from state to state. Blue catfish eat their way through estuaries and lakes, out-competing native fish populations. Plants like English ivy and multiflora rose crowd out native flowers and shrubs.

They’re called invasive because they invade. Adaptable and opportunistic, they are difficult to eradicate once established. So, when multiple agencies launched the CBNEP in 2002 to get rid of nutria at Blackwater refuge in Dorchester County and elsewhere on the Delmarva, success was not assured.

Yet despite the odds, the last confirmed nutria in Dorchester County was trapped in 2015 according to the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). The program has been so successful that the USFWS and the Mid-Atlantic Panel on Aquatic Invasive Species have recommended the techniques and equipment be adapted to an area south of the James River in Virginia that needs to control a growing nutria population. (See “Moss Balls, Whelks, and Snakeheads.”) California wildlife officials have also looked toward the Eastern Shore as a blueprint for a successful eradication program.

“It’s a heck of a lot cheaper to protect the marshes from nutria than it is to rebuild them after the fact,” said Michael L. Fies, a wildlife research biologist and furbearer project leader for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, who has been consulting with Maryland leaders to help his state eliminate its nutria populations in the early stages. “They can totally wipe out a marsh once their numbers get sufficient. But if you catch it early enough, and you don’t destroy roots, you can get it back.”

Root of the Problem

Marshes are some of the country’s most important and fragile habitats for juvenile blue crabs, grazing waterfowl, and migratory birds. They are home to non-woody vegetation that grows well in wet soil conditions, as their soil is saturated much of the year.

Marshes are dynamic, meaning they do not always stay in place. Sediment coming in on tides or during storms can help marshes remain where they are as the sediment piles up on the marsh, a mechanism known as sediment accretion. But a shortage of sediment making its way to marshes may cause marshes to disappear, through sediment erosion. These eroding marshes are replaced eventually by open water as the capture of sediment onto the marsh fails to keep pace with sea level rise. Marshes were misunderstood for many decades as managers filled them in to advance agriculture, develop land, and otherwise industrialize the nation. Today, society recognizes their ecological importance. They also may serve as living barriers during storms, absorbing wave action along the shore.

In more recent years, rising sea levels, land subsidence, and more intense storms have also threatened marshes. In Sea Level Projections for Maryland, a 2018 report that the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science prepared, “the Likely range (66% probability) of the relative rise of mean sea level expected in Maryland between 2000 and 2050 is 0.8 to 1.6 feet,” with those numbers escalating if the population does not reduce emissions. As erosion and rising water levels diminish marshes, North American wildlife such as muskrats and waterfowl compete for vegetation that is left.

Nutria only add to the problem. Adults can weigh from 15 to 20 pounds and consume a quarter of that body weight daily. Instead of grazing just the top portion of marsh plants, they dig into the soil to eat the rhizomes and the tubers, the very roots of the marsh systems. It’s not unusual for Fies, in Virginia, to return to a marsh in the morning light and find visible proof that the nocturnal invaders have munched their way through crucial habitat.

“They literally destroy the marsh vegetation, and when that vegetation dies, that results in increased erosion,” said Fies. “Then you get mudflats, and then you get open water. It causes a complete loss of the marsh.”

Nutria are indiscriminate eaters, but the plant they seem to consume the most in Blackwater refuge is Schoenoplectus americanus, also known as Olney’s three-square bulrush. This native sedge shares an ecosystem with Phragmites australis and various other semi-aquatic plants, grasses, and algae, all of which were found in nutria stomachs during a study conducted by The Wildlife Society in the 1970s, which focused on Maryland.

In 2004, a report for Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) projected the economic cost as a result of nutria damage to the marshes over the next 50 years to be $132 million when factoring in multiplier effects. The number included losses for commercial and recreational uses, including hunting, fishing, birding, and crabbing. The 2004 report cited nutria as the major culprit responsible for Blackwater refuge losing 2,905 acres from about 1954 to about 2004, representing 17 percent of the refuge’s historical marsh.

“Bay wetlands have declined for a number of reasons, including development, siltation, pollutants, and introduction of non-native species, among others,” the report states. “This erosion of wetlands continues to this day, with nutria being increasingly viewed as a major contributing factor.” And, among all of these threats, they are one of the few that managers can potentially control.

Once they’re in a system, they’re hard to stop. They become sexually mature at four months and can produce two or three litters a year, with up to 13 young in each, according to the Chesapeake Bay Program. With no natural predators, a trapping program is the only way to rid an area of them, wildlife officials say. Even then, success is uncertain. This is why even though nutria have been considered extirpated on the Delmarva since 2015, wildlife investigators still go out to look for them in case a remnant population exists or one enters the Eastern Shore from elsewhere, particularly the western side of the Chesapeake.

For his part, Fies knew his state had a problem when a motorist hit a nutria north of the James River, near the Chickahominy River northwest of Richmond. He’d never seen one there before, and he knew it wasn’t the only one. This nutria had friends.

Nutria, Before and After

These photos depict a scene that USDA officials observed many times as they canvassed the Eastern Shore’s marshes looking for nutria damage to marshes from the invasive rodent, which destroyed the plants at the root level. They were taken where Ellis Bay meets the Wicomico River in the marshy areas of the Ellis Bay Wildlife Management Area. The before image was taken while officials were determining the extent of the area’s nutria population. The after image was taken after the nutria were removed. Photos, Stephen Kendrot / USDA

2007

This photo shows “eat-outs,” areas where nutria consumed the marsh plants and their rhizomes down to the mud. In this case, they got to it “right in time,” according to Trevor Michaels, a supervisor with the Chesapeake Bay’s Nutria Eradication Project. This marsh had not reached loose mudflat or open water, considered the point of no return. The plants could still recover.

2009

In this photo, the bulrush is lush again, with nutria gone. “Once we are done, we let nature take its course,” Michaels said. “You remove the animals, and you give it a couple of growing seasons, and it will bounce back.”Nutria: A History

Fur trapping and trading between Native Americans and French and Dutch settlers was part of the American experience in the late 1600s and throughout the 1700s. Beaver pelts, and later otter pelts, were currency to trade for land, food, and even secure borders. Once colonists and foreign powers hunted fur-bearing animals to near extinction, some entrepreneurs considered farming them for their furs. As noted by A.R. Harding in his 1909 book Fur Farming, “The time is approaching when the ever-increasing demand for furs must be met by some way other than trapping the wild animals—but how? Fur farming appears to offer the only solution to the problem.”

The market for furs led enterprising importers to bring species to the United States from other countries, including two South American animals, the chinchilla and the nutria. The first US nutria fur farm appeared around 1899 in California, but disappeared a few years later. Nutria did not gain a permanent foothold in North America until 1932 in Oregon and Washington. In the late 1930s, E.L. Mcllhenny of the Avery Island Tabasco Sauce empire brought nutria to Louisiana, where they remain today.

As Americans emerged from the Depression and World War II, the get-rich-quick idea of nutria farming took hold. A 1948 ad for Blanke Nutria Farms of Wisconsin trumpeted the advantages of raising nutria for the fur industry. The ad makes its case with a string of attributes about the animals, among them that clean, easy-to-handle nutria are “easiest to raise . . . immune to disease . . . [and] adaptable to almost any climate.” It also notes that they breed early and often, producing many offspring. Finally, the ad states that breeding is “interesting, requires little work . . . and less capital to start,” and the fur produced is “truly luxurious, comparing favorably to otter”—marketing that sounded like easy money with little downside.

At Blackwater refuge, where nutria would eventually number between 50,000 and 100,000, the government helped open the door for the rodents. The USDA Fur Field Station and the USFWS shared space at the Blackwater refuge, with USFWS managing the grounds. In 1938, the USDA released some nutria into the marsh, according to historian Phillip Wingate’s book From Before the Bridge: Reminiscences. USDA officials hoped the nutria would help trappers who were dealing with a plummeting muskrat population and needed replacement fur-bearing animals to hunt.

But the entry of other breeders offering “America’s great new opportunity” during the 1940s and 1950s meant more people were getting into the nutria business, depressing the prices. In 1956, an Alabama newspaper, The Montgomery Advertiser, reported that Cajun trappers in Louisiana, the largest fur-trapping state at the time, stated that the introduction of nutria was “the worst thing that has ever happened to them.” The animals had multiplied to uncontrollable levels, and the pelts were “practically worthless.” Worst of all, the article noted, the nutria were driving out the smaller, more profitable muskrats from the marshes the two species shared.

The following year, in 1957, came another warning, from Kiplinger’s Personal Finance: “If you’re tempted by lures of quick cash to go into the nutria-raising business, think twice . . . Practically no furriers are interested in nutria. The few there are can get all they want at 50 cents to two dollars per pelt.” The Better Business Bureau expressed similar cautions later that year, but by then, many rural residents had already bet the farm, so to speak, on nutria.

It would take longer in Maryland for doubts to surface over the buck-toothed rodent. In the 1950s, M. Baker Robbins introduced six or eight pairs of nutria from Louisiana to the Eastern Shore. Fur buyer Morgan K. Bennett, who had a farm near the Choptank River, wrote classified ads around that time announcing that he had “released a few nutria in the marshes” around the Choptank. Bennett requested that trappers free them if they were caught so that “we will all have enough to trap” in the future.

But a decade later, Maryland newspapers recorded second thoughts about the wonder rodent. In 1960, USFWS’ Clifford Presnall told the Associated Press he was concerned about nutria numbers skyrocketing at Blackwater refuge, as their numbers had reached several hundred, making it appear that the invaders were “reasonably happy with Maryland’s climate,” Presnall said. Key Wallace, then the refuge’s manager, concluded the animals were “nothing but a nuisance . . . They have been burrowing our dikes . . . keeping us busy repairing them.” He added: “Our aim is to control them.”

That would prove challenging. Rather than building dens, nutria “platform” into dogpiles during winter weather, usually resulting in the death by exposure of the nutria at the top of the piles. Nutria introduction at Blackwater refuge coincided with mild winters, helping them thrive. Also, the price of nutria pelts declined. Trapping numbers in Maryland nonetheless continued upward, starting with only four trapped in 1949, increasing to 41 in 1960, reaching the thousands from 1965 to 1975, and climbing to the all-time high harvest of 29,679 in 1976.

But other factors cut into both the population and its value. Harsh winters in 1977 and 1978 killed many Delmarva nutria. The anti-fur movement that began in the 1970s in response to the harvest of seal pups gained momentum in the 1980s, spreading to all fur-bearing animals trapped for the garment trade. The stock market crash of 1987 also cut into fur business, according to The New York Times. Often dyed to resemble beaver, nutria fur had the reputation of not wearing as long and was relegated to coat linings and collars. And it failed to take off as a food item other than for novelty cook-offs. No one seemed to want to make a dietary staple out of a species that goes by the nickname “swamp rat.”

State wildlife officials had to acknowledge nutria had reached a problem level, with populations in the Blackwater, Choptank, Nanticoke, and Wicomico rivers. None other than Morgan K. Bennett, Jr., son and namesake of one of the fur dealers who had introduced nutria into Maryland, agreed. “They are just destroying the habitat,” he told The Star-Democrat in 1989. “Something’s got to be done sooner or later about these animals or we won’t have much left.”

Nutria Settle In

Today, wildlife specialists with US Department of Agriculture (USDA) are searching for nutria over a wide swath of the Delmarva Peninsula from the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel at its southern tip to the northern reaches of the peninsula. But in 2000, the search began in a much narrower region. By far, nutria’s favorite county in Maryland was Dorchester, and their preferred place in it was the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. In 2003, Congress provided funds to help eradicate nutria in Maryland. Here, we show three areas that were the initial focus of the rodent removal effort.

Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge

Currently covering over 30,000 acres, the refuge began in 1933 as a modest, 8,240-acre migratory bird refuge. In 1938, federal government officials at Blackwater released nutria into the marsh. They’d hoped the nutria would help trappers who were dealing with a plummeting muskrat population and could benefit economically from other fur-bearing animals to hunt.

Fishing Bay Wildlife Management Area

These 29,000 acres southeast of Blackwater, much of them tidal marsh, proved irresistible to nutria. The USDA trapped thousands there when it began its trapping program.

Tudor Farms

This private, 6,400-acre Dorchester estate was home to thousands of nutria. Landowners allowed federal wildlife officials to trap the creatures on their land in hopes of eradication. The marshes on either side of Tudor Farms also became thick with nutria.

Solving a Problem Like Nutria

The idea of eliminating nutria on the cheap led to offering $1.50 rebates on trapping permit fees for each nutria tail turned in at Blackwater refuge beginning in 1989, and staging nutria cooking demonstrations at the annual National Outdoor Show, which promotes conservation, education, and preservation of the outdoor-centered culture of Dorchester County. Neither really helped.

Researchers then looked to British nutria eradication programs. Harsh winters and an intensive trapping program led to the elimination—and near extirpation—of 40,000 nutria in the region of East Anglia between 1962 and 1965. In 1981, when surviving nutria re-established themselves, a second campaign took shape with the objective of eradicating them from Britain within 10 years. It relied on a three-step strategy: researching the terrain to identify the spread of nutria and their population concentrations, dividing the terrain into sectors that could be covered methodically, and returning to the same sectors to confirm eradication or conduct mop-up trapping.

In 1997, the USFWS and Maryland DNR teamed with 17 other public agencies and private groups to develop a strategy. Their pilot study concluded that it was feasible to eliminate nutria through what was termed later “repeated and ongoing culls.” A year later, Congress and President Bill Clinton signed off on a $2.9 million, three-year pilot project, and the Chesapeake Bay Nutria Eradication Program was off and running—funded by USFWS and carried out by the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s (APHIS) Wildlife Services program and other partners. Its mission was to eradicate nutria from nearly 800 square miles of Delmarva using a series of different trapping methods and then doubling back with detector dogs to make sure none remained.

A research phase from 2000 through 2002 collected data on nutria populations, behavior and movement, reproduction, and general health at three Dorchester locations: Blackwater refuge, Fishing Bay Wildlife Management Area, and Tudor Farms, a privately owned tract. The approach began with the area where the nutria were most plentiful and then moved to where they were more sporadic—beginning with Blackwater refuge, then the rest of the accessible public and private lands (with permission) in Dorchester, and then the surrounding counties. From 2002 to 2006, the collaborators began eradicating the populations with a “rolling thunder” formation of teams moving together in the same direction to cover 40-acre sectors in areas of suspected nutria populations. They followed the British model, which spread out column by column in the brackish marshes, methodically laying traps. The teams removed 4,496 nutria from Blackwater refuge in 2003.

Moving on from Blackwater refuge to other areas in Dorchester County with lower-density populations, tracking dogs brought in from Alabama and Georgia located nutria in wildlife management areas, repeatedly rechecking areas. Using this systematic strategy, the teams saw success, with the number of nutria they removed declining from 3,442 in 2004 to 540 in 2006.

The next phase expanded from Dorchester into Talbot, Caroline, Somerset, and Wicomico counties with even lower-density populations, removing as many as 1,400 in 2008 and as few as 202 in 2010, according to project officials. As the major nutria population areas were covered across the various counties, the project in 2009 began to introduce “Judas nutria”—a dozen sterilized animals equipped with radio-tracking collars. These nutria would travel up to 10 miles to seek out others of their species—indicating where populations still existed.

The Last Nutria?

In 2010, CBNEP installed floating platforms near high-travel areas at the intersection of creeks, based on the finding that nutria preferred loafing on these platforms to other spots, such as the tops of muskrat dens. Since the nutria would defecate on these platforms as well, their scat would be more likely discovered here than on flooded marsh, where scat floats and disperses with the tides. To detect the presence of nutria on these platforms, team members collected scat but also set up cameras and later installed hair snares that would catch hair for analysis when an animal passed through the platform.

As isolated captures slowed, one final group of nutria was reported by a trapper at Mud Mill Pond near the source of the Choptank River on the Maryland-Delaware border, where six nutria were removed in 2012.

In 2014, as the program was moving from the knock-down to the verification stage, it started an official detector dog program in cooperation with the USDA National Detector Dog Training Center. Program personnel were trained with mostly Labrador retriever mixes to create human-dog teams. Working from the dogs’ desire to be rewarded with a tennis ball, like Bradie, the dogs were trained to sniff out nutria scat and other samples taken from nutria in captivity at Blackwater refuge. The detector dogs remain local after their work in the program; in many cases, their handlers adopt them.

The detector dogs found 16 nutria in early 2015 at the Ellis Bay Wildlife Management Area at the mouth of the Wicomico River. Those were among the last nutria found on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Now, the program is well into its verification phase. CBNEP human-dog teams retrace their steps, checking every sector where eradication has taken place. Pepper said they are out almost every day, and with two refrigerators full of nutria scat samples, they are always testing the dogs with different scents.

The effects of climate change, land subsidence, and sea level rise point to a grim fate for Blackwater refuge and other Delmarva marshes. But at least scientists and managers can point to the collaborative nutria eradication effort as a success that has strengthened these critically important places against an uncertain future, and as an inspiration for those trying to protect other jeopardized habitats.

“It was absolutely successful,” Pepper said, adding that she’s gotten calls from as far away as Israel and China for advice on eradicating their nutria. “A lot of lessons were learned along the way, and that is the true value. Now, we can help these other places.”

Phillip Hesser is a writer, historian, and educator focusing on the landscape, life, and livelihoods of Delmarva and the Chesapeake Bay watershed. His latest book, co-authored with Charlie Ewers, is Harriet Tubman’s Eastern Shore—The Old Home Is Not There.

Rona Kobell is the editor of Chesapeake Quarterly.

![[Maryland Sea Grant]](/images/uploads/siteimages/CQ/MD-Logo.png)