|

The Colorful (and Disappearing) World

of Bay Biodiversity

Daniel Strain

Robert Reynolds, seen here admiring a coiled snake preserved in a mixture of formalin and alcohol, says that his team has yet to collect all of North and Latin America’s amphibians and reptiles. Credit: Daniel Strain.

ROBERT REYNOLDS COULD GET LOST among all these jars.

Right now, the soft-spoken scientist is touring the Smithsonian Institution's amphibian and reptile collection, housed in a massive annex in Suitland, Maryland, called the Museum Support Center. The whole place seems like it's overflowing with glass containers — and there are, in fact, hundreds of thousands of them here. The jars are spread across three huge rooms and are neatly stored on dozens of metal shelves.

And in each one, there's a deceased animal. Or sometimes many, all floating in clear to honey-colored preserving fluid. A good-sized fraction are from North America, including some that roamed the Chesapeake Bay region when they were alive. We walk past salamanders from the Blue Ridge Mountains, tadpoles from eastern Virginia, venomous snakes, and juvenile turtles the size of a half-dollar. But what Reynolds, a scientist who's based at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, seems to prize most about this collection is its diversity and organization.

To illustrate, he stops in an aisle and picks up a jar at random. Four cream-colored salamanders with black spots are suspended inside. They belong to the species Notophthalmus viridescens, or the Eastern newt, and were caught in western Virginia. Inside are numbers 556,994 to 556,997, Reynolds says, reading the jar's printed label.

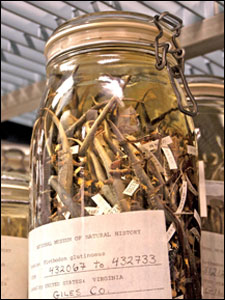

Northern slimy salamanders (Plethodon glutinosus) collected from the mountains of Virginia bob inside one of the thousands of jars in the Smithsonian Institution's amphibian and reptile collection.

Credit: Daniel Strain.

Sure enough, each salamander inside has a small tag tied around its tiny ankle that bears its six-digit ID number, beginning with 556,994. As that number suggests, there are well over half a million reptiles and amphibians in this collection. The oldest ones from the 1800s were collected before formalin, a common preservative, was in wide use, so they were stored in whatever was on hand, often grain alcohol or rum. Reynolds himself has dabbled in that. Lacking better options, he once brought home a bat he had caught in Mexico in a bottle of cheap tequila.

So with a collection this eclectic and this huge, you can see why Reynolds is obsessed with order.

"If you misplace a jar in this collection, it is lost," says Reynolds, who directs the U.S. Geological Survey's Biological Survey Unit, a group that collects and curates North and Latin American vertebrates, or animals with backbones, for the museum.

It's a good reminder of the sheer scope of the Smithsonian's biological collections and of North America's biodiversity. There are so many animals and plants out there for Reynolds and others like him to discover.

But in the wilds of Maryland and elsewhere, many of the animals preserved here are also vanishing at an alarming rate — like the Maryland darter (Etheostoma sellare), a small and yellowish fish that hasn't been seen since 1988.

The Biodiverse Bay

Biodiversity is a fluid term with any number of definitions. It can refer to the total number of species living in an ecosystem. But it can also describe the diversity of functions that different organisms perform within an ecosystem. Or even the diversity within a single species.

In a simple sense, the term describes variety in the forms and shapes of life. Wade into a stream, dig up a clump of dirt in your garden, or turn over a log in a forest and you'll see it: lots of wriggling, crawling, swimming, or leafy life.

Putting a number on that variety has never been easy. Even in regions as well studied as the Chesapeake Bay watershed, there are still a lot of animals and plants on land and in the water that are small, rare, and hard to count.

Maryland's Natural Heritage Program, which monitors rare and endangered species regionally, keeps those tallies. The program recognizes 1,232 vertebrates as native to the state, including 635 fish and 21 salamanders. The Chesapeake Bay Program, a coalition of state and federal agencies, estimates that more than 2,700 species of animals and plants live throughout the Bay.

Those numbers, while high, can't compare to the biodiversity that you'd find in a tropical region. And, in fact, when the topic of biodiversity comes up, talk almost always turns to rainforests or coral reefs. But the Chesapeake Bay's biodiversity is no less important to its health and proper functioning. Even scarce species like the Shenandoah salamander (Plethodon shenandoah), which is known to live on only three mountains in Virginia, contribute.

"The plants and animals that are here, they evolved together," Reynolds says. "They have this incredibly tight, synergistic network that functions amazingly well."

In other words, the region's plants and animals fill unique roles in their environments. Although many people argue for preserving this web of life for moral or aesthetic reasons, there's also a practical benefit that can be expressed in dollars and cents. In the Chesapeake region, marsh plants trap pollutants coming from streams and rivers, small fish like menhaden provide food for bigger fish like striped bass, and trees absorb carbon dioxide from the air — all actions that the Bay's human residents depend on.

Increasingly, economists have worked to estimate monetary values on these "ecosystem services," which globally may run into the trillions of dollars (see Small Wonders).

Studies indicate that greater diversity of species makes natural communities more stable and productive. This generates more ecosystem services and helps the ecosystem to survive environmental changes more easily.

"If the entire world becomes corn and cockroaches and starlings and six or eight species that live pretty well with humans, it's not only going to be spiritually depauperate," says Emmett Duffy, a scientist who studies marine biodiversity at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science in Gloucester. "But we're also going to be in big trouble."

Biodiversity Loss

In Maryland and other states around the Bay, salamanders like the ones in Reynolds’s jars are in trouble. They live in the streams and pools that trickle down to the Chesapeake Bay. Many are sensitive to even tiny changes in temperature or pollution levels in those waters, making them important bellwethers for the state of local waterways.

And many, like the Eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis), aren’t doing too well. This giant of a salamander, which looks like a river boulder, has grown rarer and rarer in the mountains of western Maryland, likely because of the loss of good streams there.

Globally, signals of trouble are visible in the large number of species at risk of extinction and the unusually high rate at which species are vanishing.

Scientists estimate that the extinction rate today is 100 to 1,000 times higher than the “background” or average extinction rate during the history of life on earth. If that’s the case, half of all living species could slip away by 2100.

Shrinking habitats, increasing pollution levels, invasive species, climate change, and an array of other challenges have slowly pared away the world’s plants and animals. Worldwide, around 25 percent of mammal species, 30 percent of freshwater crabs, and 40 percent of amphibians are threatened, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a conservation group.

Scientists will tell you that it’s hard to accurately measure the scale of biodiversity loss, both around the world or in an area like the Chesapeake watershed. In our region, though, there are certainly marquee examples. In part because of the zeal of watermen that sought their roe, only a few hundred spawning Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) live in the Chesapeake region today, most of them in the James River.

Maryland Species at Risk

Maryland darter

(Etheostoma sellare)

Discovered in 1912, this small fish was known as the only vertebrate that lived in Maryland and nowhere else.

Eastern hellbender

(Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis)

These salamanders, which can grow to more than two feet long, live exclusively underwater.

Atlantic sturgeon

(Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus)

Atlantic sturgeon grow to about six feet long and have a row of bony plates running down their sides. Their ancestors date back to the time of the dinosaurs.

Bog turtle

(Glyptemys muhlenbergii)

Bog turtles, found in swamps and marshes, are the smallest turtles in North America, measuring only about 4 inches long.

Dwarf wedgemussel

(Alasmidonta heterodon)

The microscopic larvae of dwarf wedgemussels spread far and wide by hooking themselves onto the bodies of swimming fish.

Image credits: Maryland darter, David Neely; Eastern hellbender, Brian Gratwicke, Wikimedia Commons; Atlantic sturgeon, Duane Raver; bog turtle, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; and dwarf wedgemussel, Susi von Oettingen, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

An estimated 128 species have already been lost from Maryland. Deep in the Smithsonian’s archives, for instance, sit a handful of specimens of the Maryland darter. Scientists were lucky to catch the fish in 1965 — even then, it could only be found in a few small creeks that flowed into the Susquehanna River near Aberdeen, Maryland. Today, the specimens are some of the last reminders of the darter’s existence. For reasons that remain unclear, the fish hasn’t been seen since 1988.

In all, Maryland’s Natural Heritage Program lists 345 plants and 139 animals as endangered, threatened, or in need of conservation in Maryland — meaning they run the risk of following the darter’s fate. But being listed doesn’t guarantee that a species will recover.

Such figures touch on only part of the picture, says Maile Neel, who studies rare and endangered plants at the University of Maryland, College Park. Many species are in decline, even if their populations are still too large to land them on an endangered species list. “You may have the species still here, but 90 percent of their populations are gone,” says Neel, an associate professor of plant science and landscape architecture. “That’s a decrease in biodiversity, but those [cases] are really hard to quantify.”

For other species, scientists haven’t even realized that losses are occurring, Neel says. There simply haven’t been enough scientists to detect declines in many obscure species, such as insects or crustaceans living in bay-grass beds. Around the Chesapeake, species may be going extinct before scientists have had the chance to discover or name them.

The end result is that although scientists are sure that biodiversity loss has happened and is still happening here, no one knows exactly how large that loss is. But the consequences for the entire ecosystem seem sizeable in certain cases, especially that of an iconic Bay species, the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Although these bivalves aren’t listed as an endangered species in Maryland or Virginia, their numbers in the Chesa¬peake Bay are at less than one percent of historic levels. And because these organisms filter sediments and nutrients from the Bay, their loss may have had a large impact on water quality and the ecosystem.

Scientists agree that the global loss of biodiversity is a big deal. In a paper published in Nature in 2012, researchers suggested that it could have as much of an impact on the proper functioning of ecosystems as many other environmental conditions that are damaging them. Those include climate change and nutrient pollution, both sizable concerns on the Chesapeake.

Reynolds, surveying his jars, notes another loss: the scientists who study biodiversity, he says, have experienced their own population declines. Because of budget cuts, many museums have trimmed back on their staff considerably. Reynolds has watched as his colleagues retired one by one without younger scientists coming to replace them. Museum collecting and curating also isn’t as popular a field as it once was — maybe because it’s viewed as stodgier than other disciplines at the forefront of scientific innovation.

“The irony is, at the time when biodiversity is more in the news today than ever previously, there are fewer and fewer people and fewer dollars to support it,” Reynolds says.

But Reynolds and his colleagues have continued to build their collections, even as many other museums have shut theirs down. And his jars are a profound reminder that there’s still a lot of biodiversity left to protect. Scientists say that preserving species will depend on solving difficult and potentially costly challenges in the management of natural resources in Maryland and worldwide. Those challenges include mitigating and adapting to climate change, stopping the spread of invasive species, preserving natural habitats, and reducing the flow of excess nutrients into waterways.

Reynolds says he certainly holds out hope for the future. “Am I hopeful? Absolutely,” he says. “I’m a realist. But I’m hopeful.”

That’s something worth preserving — no museum collection jar required.

|